Human civilisation has developed dozens of writing systems over millennia, each reflecting the unique linguistic, cultural, and historical contexts of its users. From the flowing curves of Arabic to the geometric precision of Korean Hangul, these scripts represent humanity’s enduring quest to capture language in visual form. This article explores the major writing systems used around the world today.

The Latin Alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the most widely used writing system in the world. Originally developed by the ancient Romans from the Etruscan alphabet (which itself derived from Greek), it has become the script of choice for hundreds of languages across Europe, the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and parts of Asia.

The basic Latin alphabet consists of 26 letters, though many languages extend it with diacritical marks and additional characters. Spanish adds the ñ, French uses accents like é and è, German includes umlauts (ä, ö, ü), and Scandinavian languages feature letters like å, æ, and ø. Vietnamese, despite being a Southeast Asian language, adopted a Latin-based script in the 17th century, complete with an elaborate system of tone marks.

The alphabet’s dominance spread through Roman conquest, Christian missionary work, European colonialism, and more recently, globalisation and digital technology. Its relatively simple structure, representing individual consonants and vowels, makes it adaptable to many different languages, though not always perfectly.

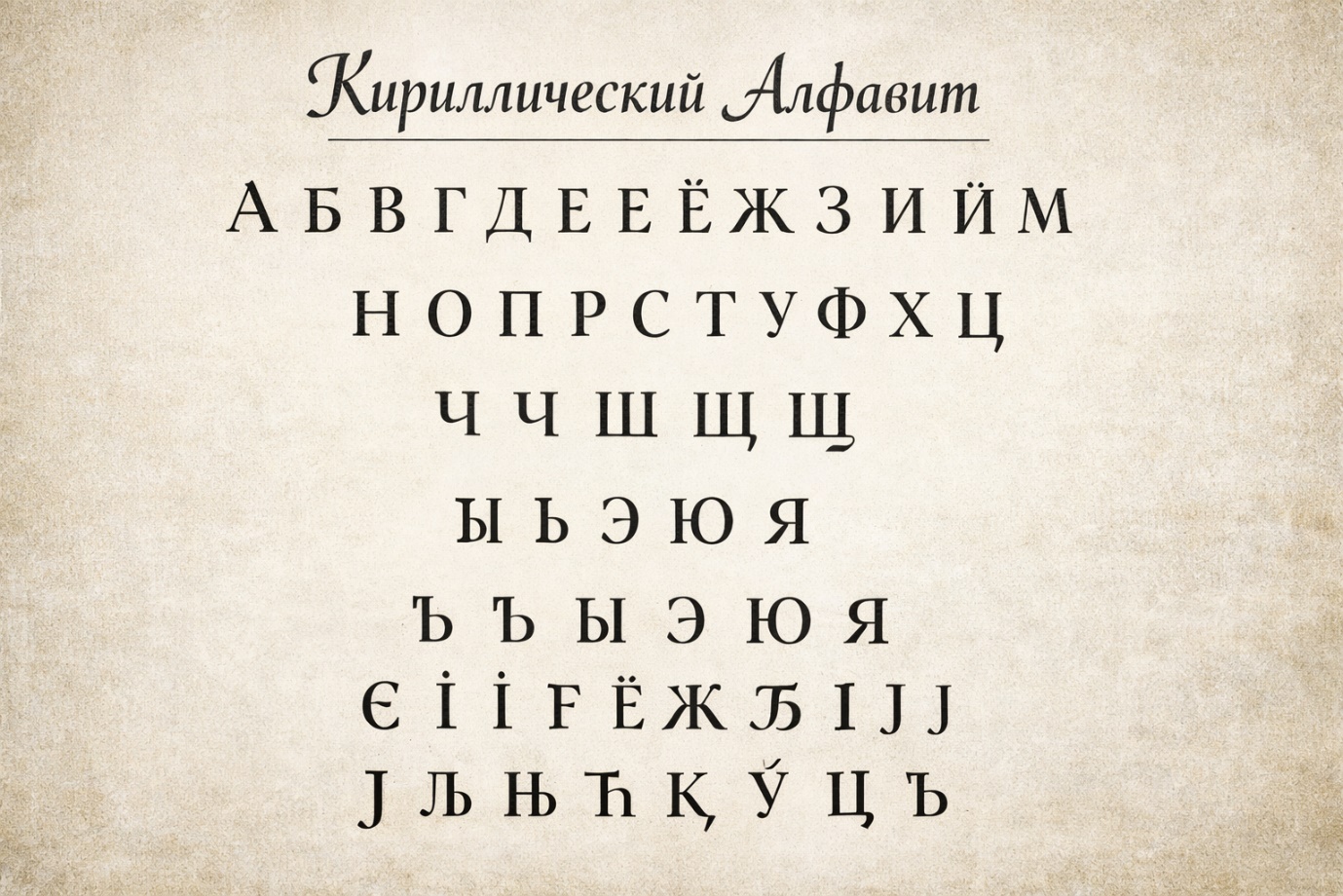

The Cyrillic Alphabet

The Cyrillic alphabet serves as the writing system for Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Macedonian, and many other languages across Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Created in the 9th century by the Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius (or their disciples), Cyrillic was designed specifically to write Slavic languages.

The Russian Cyrillic alphabet contains 33 letters, while other languages using Cyrillic scripts may have more or fewer characters adapted to their phonetic needs. Letters like А, Е, К, М, О, and Т look identical to Latin letters, while others like Д, Ж, Л, Ф, and Я are distinctively Cyrillic. Some letters appear similar to Latin but represent entirely different sounds, В represents the “v” sound, Р is “r”, and Н is “n”.

Different Slavic nations have modified the basic Cyrillic alphabet to suit their languages. Serbian and Macedonian include letters not found in Russian, while Ukrainian has its own unique characters. The alphabet’s flexibility has allowed it to be adapted for non-Slavic languages too, including Mongolian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and various languages in the Caucasus region.

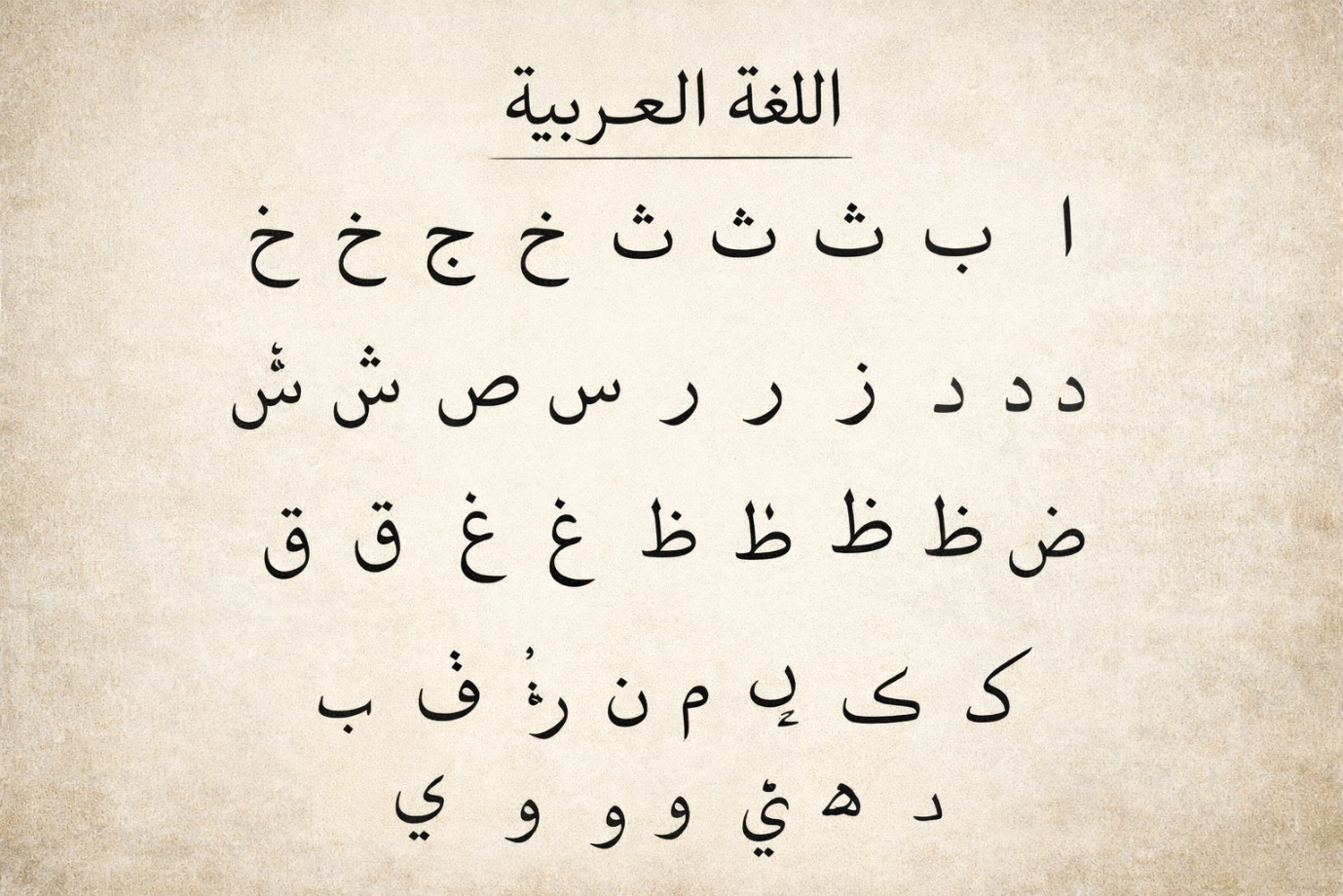

The Arabic Alphabet

The Arabic alphabet is the second most widely used writing system in the world, serving as the script for Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Pashto, Kurdish, and numerous other languages across the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia. Its elegant, flowing form has made it a celebrated art form in Islamic calligraphy.

The Arabic script contains 28 basic letters, all representing consonants and long vowels. Short vowels are typically indicated by diacritical marks above or below letters, though these are often omitted in everyday writing. One of the script’s distinctive features is that letters change shape depending on their position in a word, whether they appear at the beginning, middle, end, or in isolation.

Arabic is written from right to left, a characteristic it shares with Hebrew and a few other scripts. The connected, cursive nature of Arabic writing means that most letters link to their neighbours, creating a continuous flow across the page. This cursive quality has elevated Arabic calligraphy to one of Islam’s highest art forms, with styles ranging from the angular Kufic to the flowing Naskh and elaborate Thuluth.

Persian (Farsi) and Urdu have added several letters to the basic Arabic alphabet to represent sounds that don’t exist in Arabic. Despite using the same script, these languages have developed their own distinct calligraphic traditions and aesthetic preferences.

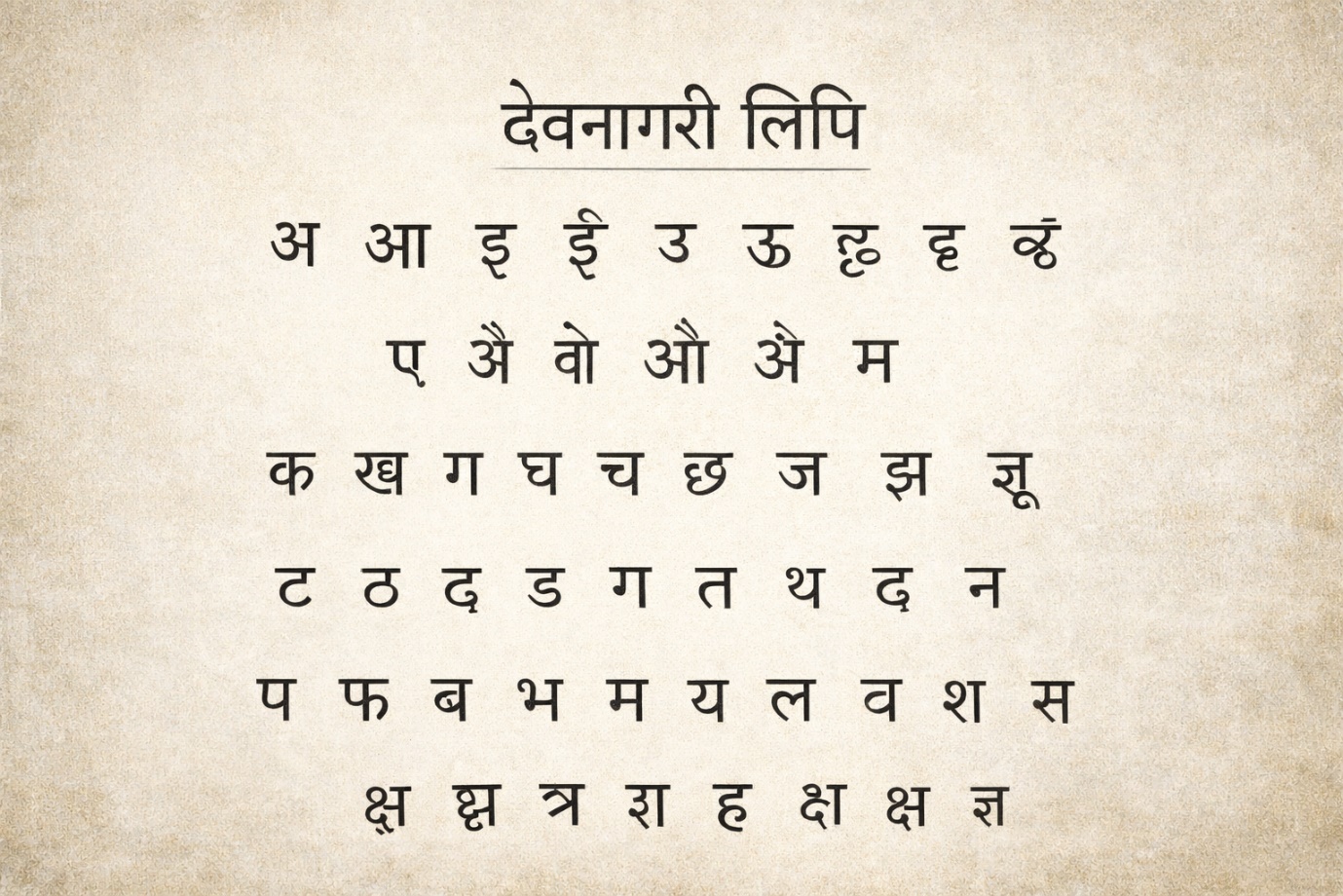

The Devanagari Script

Devanagari is the primary writing system for Hindi, Marathi, and Sanskrit, and is also used for Nepali and several other languages. With over 600 million users, it ranks among the world’s most widely used scripts. Its name combines “deva” (divine) and “nagari” (city), reflecting its sacred associations with Sanskrit, the liturgical language of Hinduism and Buddhism.

Devanagari is an abugida, meaning each consonant letter carries an inherent vowel sound (usually “a”), which can be modified by adding vowel marks above, below, or beside the consonant. The script includes 11 vowels and 33 consonants in its basic form, plus numerous conjunct characters formed by combining consonants. A distinctive horizontal line, called a shiro-rekha, runs along the top of the letters in each word, connecting them visually.

The script’s systematic organisation reflects ancient Indian linguistic science. Consonants are arranged by their place of articulation (from the throat to the lips) and manner of articulation (stops, nasals, etc.). This logical structure made Devanagari relatively easy to adapt for different Indian languages, and it has influenced the design of other Indian scripts.

Reading Devanagari requires recognising not just individual letters but also the numerous ligatures formed when consonants combine. Words like “श्री” (shri) merge multiple consonants into a single visual unit, a feature that gives Devanagari texts their distinctive appearance.

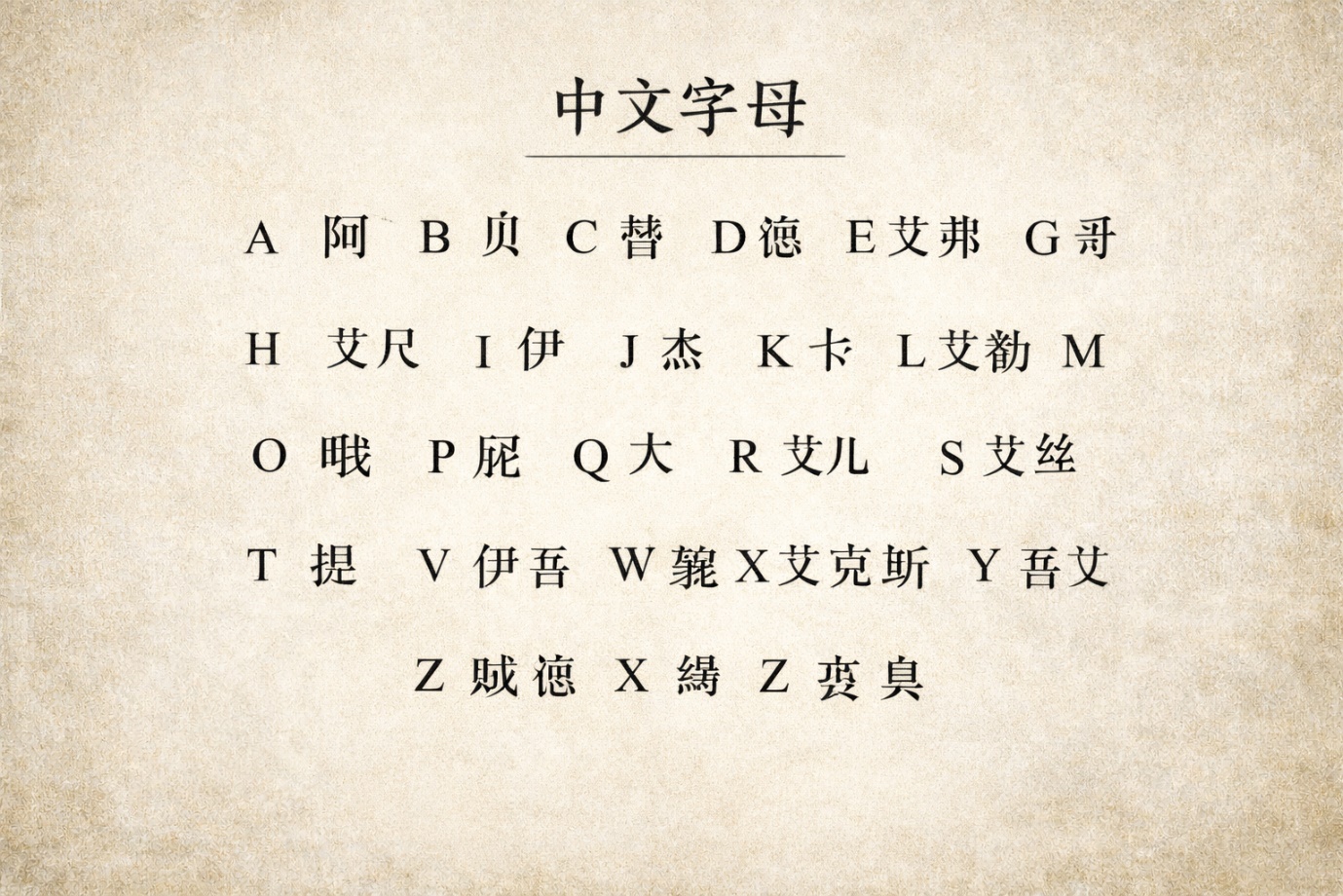

Chinese Characters

Chinese characters, or hanzi, represent one of the world’s oldest continuously used writing systems, with a history spanning over 3,000 years. Unlike alphabetic systems, Chinese uses logographic characters where each symbol typically represents a morpheme, a unit of meaning, rather than a sound.

The Chinese writing system contains tens of thousands of characters, though literacy requires knowledge of about 3,000 to 4,000 common ones. Characters range from simple forms like 人 (person) and 口 (mouth) to complex ones like 鬱 (melancholy), which contains 29 strokes. Most characters are composed of semantic components (suggesting meaning) and phonetic components (hinting at pronunciation).

Mainland China simplified many characters in the 1950s to improve literacy, creating what are now called simplified characters. Taiwan, Hong Kong, and overseas Chinese communities continue to use traditional characters. For example, the word for “dragon” is written as 龙 in simplified form and 龍 in traditional form.

Chinese characters have profoundly influenced East Asian writing systems. Japanese kanji are adapted Chinese characters, Korean historically used Chinese characters called hanja, and Vietnamese used Chinese-derived characters until adopting the Latin alphabet in the 20th century. This shared script once served as a lingua franca for East Asian educated elites, much as Latin did in medieval Europe.

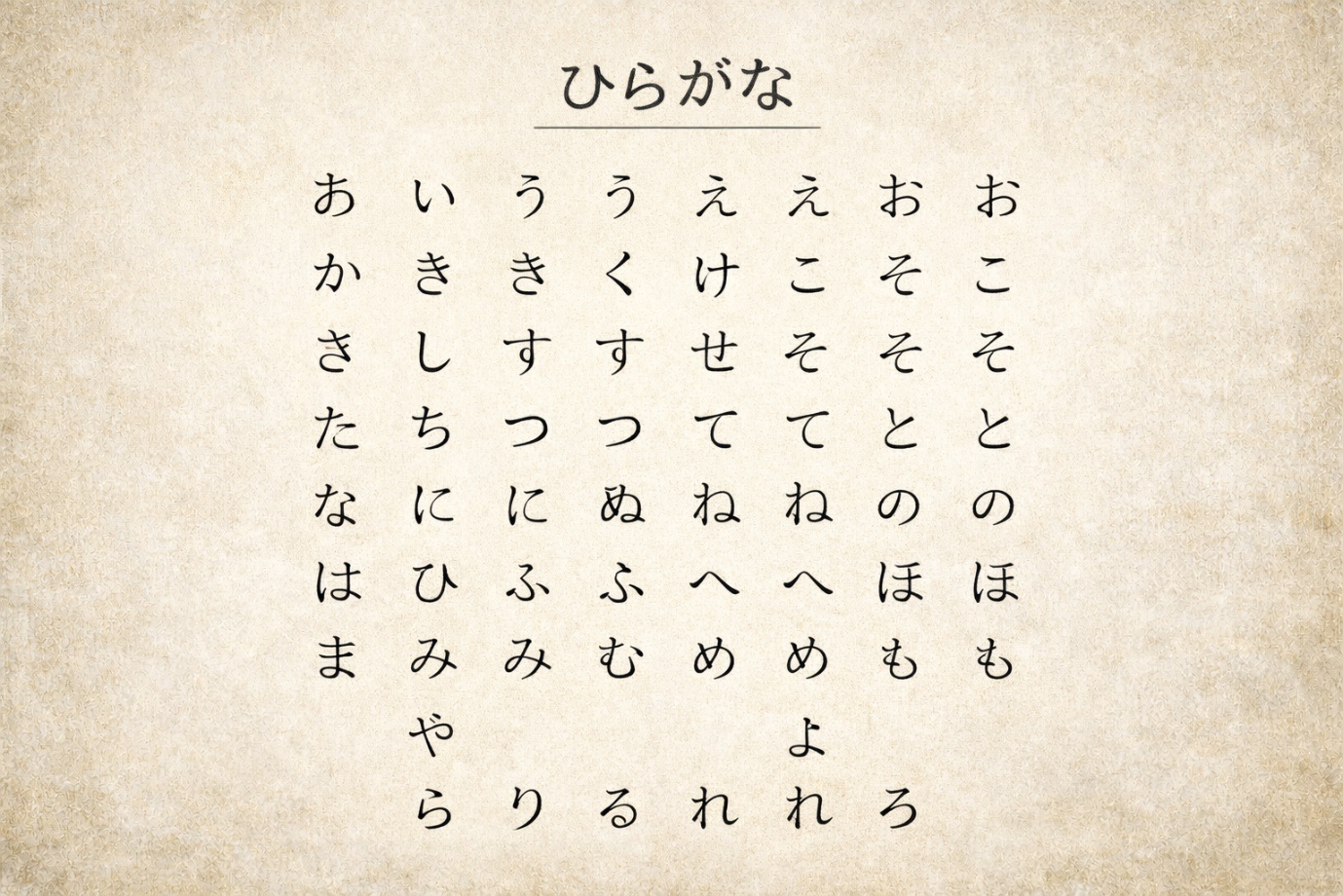

Japanese Writing System

Japanese employs one of the world’s most complex writing systems, simultaneously using three different scripts: kanji (Chinese characters), hiragana, and katakana. This trilateral system reflects Japan’s unique linguistic history and the layers of cultural influence it has absorbed.

Kanji, borrowed from Chinese, represent content words and word stems. A typical Japanese text uses about 2,000 kanji, though educated readers know more. Japanese pronunciations of kanji often include both on-yomi (Chinese-derived readings) and kun-yomi (native Japanese readings), making the system intricate.

Hiragana is a syllabic script with 46 basic characters, each representing a syllable. It’s used for native Japanese words, grammatical particles, verb endings, and words written in kanji that are deemed too difficult. The flowing, cursive appearance of hiragana reflects its origins as a simplified form of kanji used initially by women in the Heian period.

Katakana, also consisting of 46 basic characters corresponding to the same syllables as hiragana, has a more angular appearance. It’s primarily used for foreign loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and emphasis (similar to italics in English). Words like “computer” (コンピューター) and “coffee” (コーヒー) are written in katakana.

A single Japanese sentence might read: 私はコーヒーを飲みます (I drink coffee), combining kanji (私, 飲), katakana (コーヒー), and hiragana (は, を, みます).

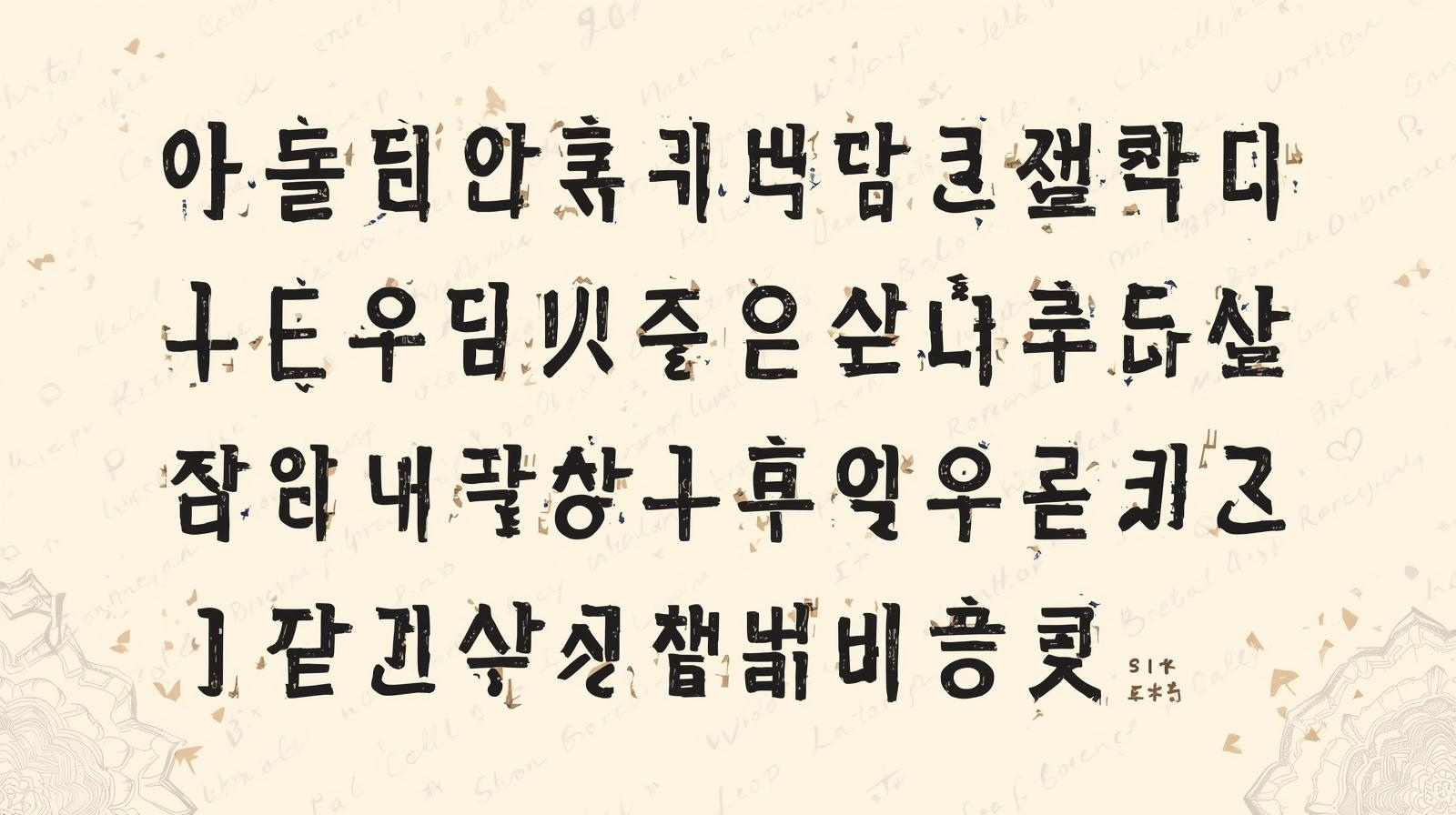

Korean Hangul

Hangul, the Korean alphabet, stands out as one of the few writing systems whose origin, purpose, and creator are precisely documented. King Sejong the Great commissioned its creation in 1443, and it was promulgated in 1446. Before Hangul, Korean was written using Chinese characters, which were poorly suited to representing Korean grammar and sounds.

Hangul consists of 24 basic letters, 14 consonants and 10 vowels. What makes it unique is its featural design: the shapes of consonant letters visually represent the position of the tongue, lips, and throat when making those sounds. For instance, ㄱ (g/k), ㄴ (n), ㅁ (m), and ㅅ (s) each suggest the articulatory features of their sounds.

Rather than writing letters in a linear sequence, Hangul arranges them into syllable blocks. The word “Hangul” itself (한글) is written as two blocks: 한 (han) and 글 (gul), with each block containing two or three letters arranged spatially. This syllabic organisation gives Korean text a compact, balanced appearance while maintaining the efficiency of an alphabetic system.

Linguists often praise Hangul as one of the most scientific and logical writing systems ever created. Its systematic design makes it relatively easy to learn, UNESCO celebrates the anniversary of its creation as World Literacy Day, acknowledging its contribution to accessible written communication.

The Greek Alphabet

The Greek alphabet holds a special place in the history of writing systems. Developed around the 8th century BCE, it was the first alphabet to represent vowels explicitly as independent letters rather than optional diacritics. This innovation made Greek writing more precise and accessible than earlier Semitic scripts.

The Greek alphabet contains 24 letters, from alpha (Α, α) to omega (Ω, ω). It’s used today primarily for modern Greek but has left an indelible mark on Western civilisation. The Latin and Cyrillic alphabets both descended from Greek, and Greek letters permeate scientific and mathematical notation, π for pi, Σ for summation, Δ for change, and α, β, γ for labelling series.

Ancient Greek was written in various regional variations, eventually standardising into Classical Greek forms. Modern Greek has evolved both the letterforms and pronunciation, though the alphabet remains largely unchanged. The script is written from left to right, with both uppercase and lowercase forms for each letter.

Greek’s influence extends beyond its direct descendants. English and other European languages have borrowed thousands of Greek words and roots, often retaining Greek letters in scientific contexts. Terms like “phi phenomenon,” “beta testing,” and “delta wing” preserve Greek letters in specialised vocabulary.

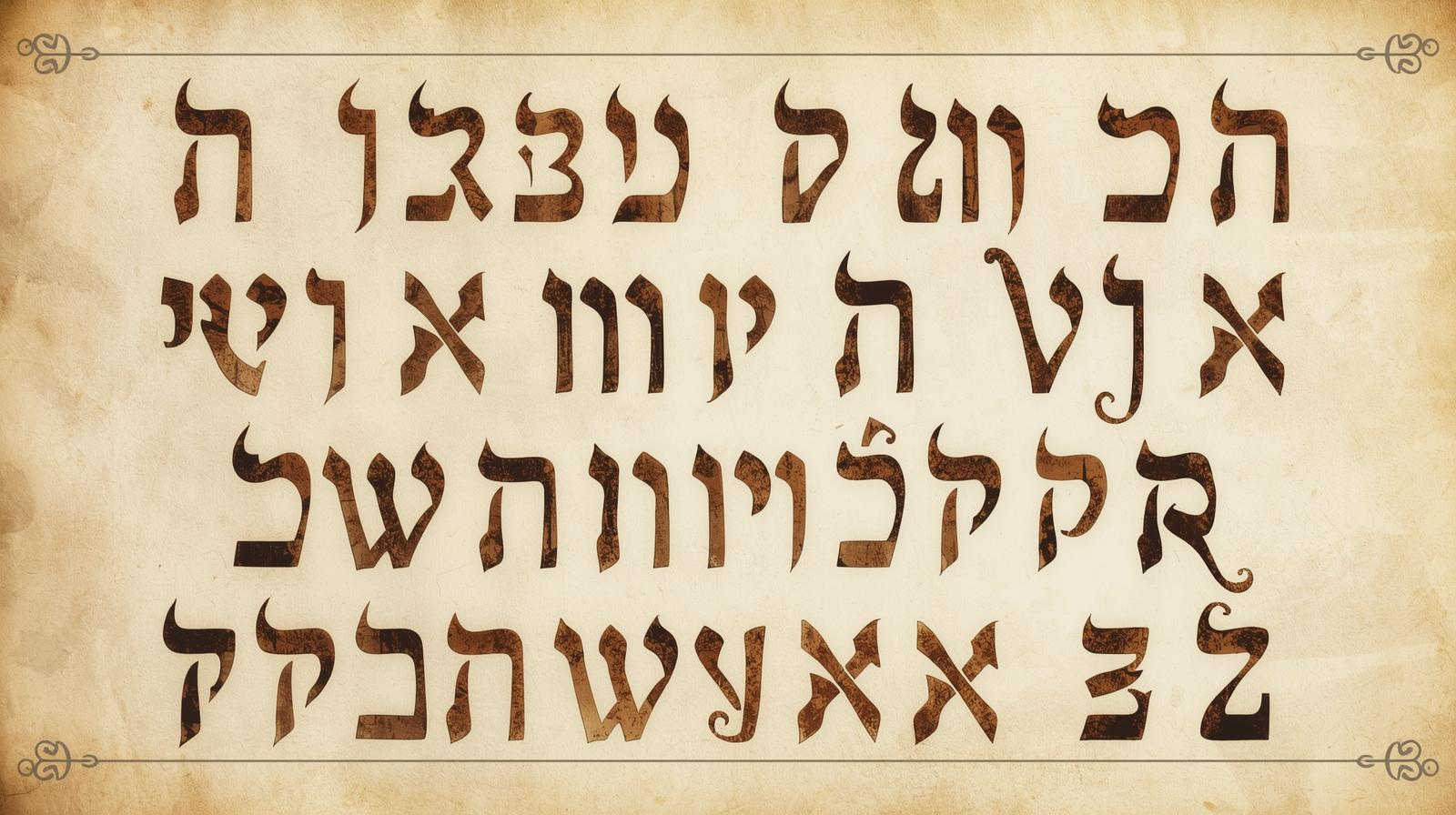

The Hebrew Alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet, or aleph-bet, is one of the oldest writing systems still in use today, with roots tracing back over 3,000 years to ancient Semitic scripts. It serves as the writing system for Hebrew and Yiddish, and is used in Jewish religious texts regardless of the language being written.

Hebrew contains 22 letters, all representing consonants. Like Arabic, it’s written from right to left. The script doesn’t include letters for vowels; instead, vowel sounds are indicated by a system of dots and dashes called nikud, placed above, below, or inside letters. However, nikud is typically used only in religious texts, children’s books, poetry, and texts for language learners. Experienced readers infer the vowels from context.

Several letters have different forms when they appear at the end of a word (sofit forms), and the script exists in both printed and cursive styles. The printed form is called “square script” due to its angular, geometric appearance, while the cursive form flows more freely and is used in handwriting.

Hebrew letters also serve as numbers in traditional contexts. Aleph (א) equals 1, bet (ב) equals 2, and so on, a system called gematria. This numerical aspect has inspired extensive mystical and interpretive traditions in Jewish thought, particularly in Kabbalah.

Southeast Asian Scripts

Southeast Asia is home to numerous related writing systems descended from ancient Indian scripts through the spread of Buddhism and Hinduism. These abugida scripts share common characteristics but have evolved distinct identities.

Thai script, with its circular forms and absence of spaces between words, writes the Thai language and is also used for several minority languages in Thailand. It includes 44 consonant letters, vowel signs that appear above, below, or around consonants, and tone marks that sit above letters to indicate the language’s five tones.

Lao script, closely related to Thai, serves the Lao language with similar principles but slightly different letter forms. Burmese script’s highly curved, circular letters reflect the practice of writing on palm leaves, where straight lines might cause tears. Khmer script, used for Cambodian, features ornate forms that have remained remarkably stable since ancient times.

These scripts all treat consonants as base letters carrying an inherent “a” vowel, with additional marks modifying the vowel sound. They write from left to right and traditionally don’t use spaces between words, only between phrases or sentences. Each has developed its own calligraphic traditions and is deeply intertwined with Buddhist textual culture.

African Alphabets

Africa’s linguistic diversity has produced numerous indigenous writing systems alongside scripts introduced through trade, colonisation, and religious conversion. The continent uses Latin, Arabic, and several unique African alphabets.

Ge’ez script, also called Ethiopic, is an ancient abugida used for Amharic, Tigrinya, and other Ethiopian and Eritrean languages. Dating back nearly 2,000 years, it’s one of the world’s oldest continuously used writing systems. Unlike most abugidas, Ge’ez explicitly marks all vowels, making it almost a true alphabet.

N’Ko script, created in 1949 by Guinean scholar Solomana Kante, serves several Mande languages in West Africa. Written right to left like Arabic, it has become a symbol of West African cultural identity and linguistic independence.

Vai script from Liberia is one of the few indigenous African scripts created without external influence, developed in the early 19th century. It’s a syllabary where each character represents a consonant-vowel combination.

Several other African writing systems have emerged in modern times, including Tifinagh (for Berber languages), Osmanya (for Somali), and Mandombe (for Bantu languages). These scripts represent both ancient traditions and contemporary movements to express African languages in culturally authentic forms.

Conclusion

The world’s diverse writing systems reflect humanity’s creativity in capturing language visually. From the logical efficiency of Korean Hangul to the artistic beauty of Arabic calligraphy, from the ancient continuity of Chinese characters to the scientific precision of the Greek alphabet, each script embodies the linguistic and cultural values of its users.

In our globalised age, many scripts coexist within single societies, and individuals increasingly navigate multiple writing systems. Technology has made fonts for virtually every script accessible, preserving and promoting writing traditions that might otherwise be endangered. Yet challenges remain, as many minority scripts struggle for recognition and standardisation in the digital realm.

Understanding these writing systems offers more than linguistic knowledge, it provides windows into different ways of thinking about language, meaning, and communication. Each script tells a story of human ingenuity, cultural exchange, and the enduring power of the written word to preserve and transmit human knowledge across space and time.

Leave a Reply