Perched on Ayasuluk Hill in the Turkish town of Selçuk, the ruins of the Basilica of St. John the Evangelist stand as a powerful testament to early Christian devotion and Byzantine architectural ambition. Though now reduced to columns and foundations, this once-magnificent church was among the most important pilgrimage sites in the Christian world, built to honour one of Jesus’s closest disciples.

The Sacred Tradition

The basilica’s significance stems from an ancient Christian tradition that John the Evangelist, author of the Fourth Gospel, spent his final years in Ephesus, just a short distance from modern Selçuk. According to this belief, John came to the city with the Virgin Mary, established a Christian community, and was eventually buried on Ayasuluk Hill. Early Christians marked the spot with a modest memorial, which became a focus of veneration for centuries.

Imperial Ambition: Justinian’s Grand Vision

The transformation of this humble shrine into a grand basilica came in the 6th century under Emperor Justinian I, one of Byzantium’s most ambitious rulers. Reigning from 527 to 565 AD, Justinian sought to revive the glory of the Roman Empire and reinforce orthodox Christianity throughout his domains. He commissioned magnificent churches across the empire, most famously the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Around 548 AD, Justinian ordered the construction of an enormous basilica over John’s supposed burial site. While the specific architect’s name hasn’t survived in historical records, unlike the documented architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, who designed Hagia Sophia, the building clearly reflected imperial Byzantine architectural expertise and ambition.

Architectural Splendour

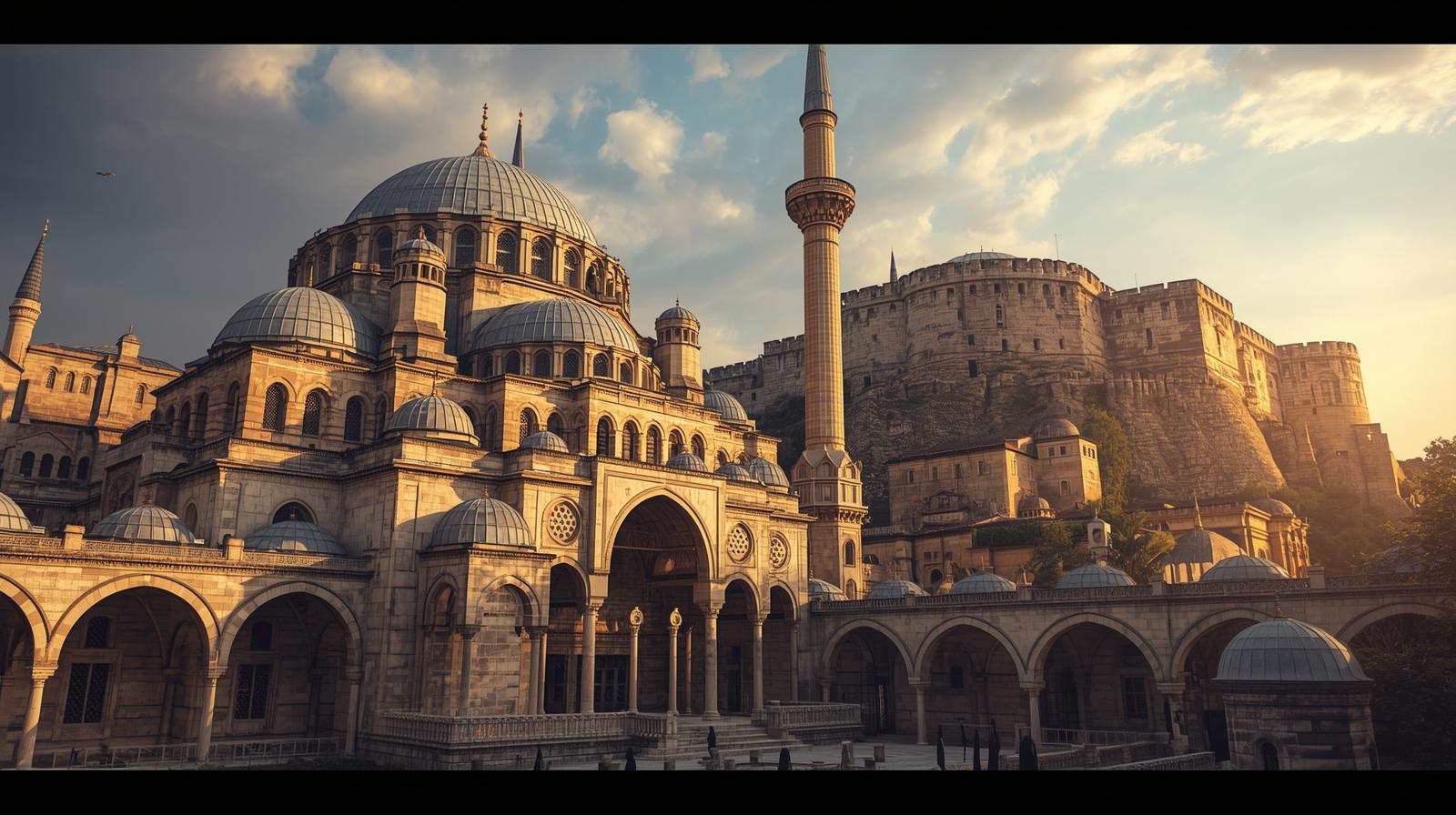

The basilica followed a cruciform plan, shaped like a cross, and was built primarily of stone and brick. The church stretched approximately 130 metres in length, making it one of the largest Byzantine churches of its era. Six massive domes crowned the structure, creating a dramatic skyline that would have dominated the landscape.

2

The design featured a central nave flanked by aisles, with the focal point being the tomb of St. John beneath the central dome. Marble columns supported the arcades, many of which still stand today, giving visitors a sense of the building’s original scale. The floors were decorated with intricate mosaics, and the walls likely bore frescoes celebrating John’s life and ministry.

A baptistery stood adjacent to the main church, where converts would have been initiated into the Christian faith through the sacrament of baptism, a common feature of major Byzantine churches.

Centuries of Use and Transformation

For centuries, the basilica served as an active centre of Christian worship and pilgrimage. It functioned as a cathedral and became particularly important after the Arab raids of the 7th and 8th centuries made the coastal city of Ephesus increasingly vulnerable. Selçuk, with its more defensible hillside position, grew in importance.

The church suffered damage from Arab raids but was restored multiple times during the Byzantine period. In 1090, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos ordered significant repairs. However, the basilica’s fate was sealed by a combination of factors: earthquakes damaged the structure, and the region’s conquest by the Seljuk Turks in the late 11th century ended its function as a major Christian centre.

By the 14th century, a small mosque had been built within the ruins, and the site gradually fell into further decay. For centuries, local residents quarried its stones and columns for other building projects.

A Major Pilgrimage Destination

During its active centuries, the Basilica of St. John was indeed a crucial stop on pilgrimage routes. Christian pilgrims travelling from Europe to the Holy Land would often include Ephesus and St. John’s tomb in their itinerary. The site ranked alongside Jerusalem, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela as one of Christianity’s most sacred destinations.

Medieval pilgrims believed that dust from John’s tomb possessed miraculous healing properties. They would collect small amounts to take home, and numerous accounts survive of pilgrims experiencing visions and healings at the site. The basilica also housed other important relics, further enhancing its appeal.

The Basilica Today

Modern visitors to Selçuk encounter an evocative archaeological site rather than a functioning church. Systematic excavations began in the 1920s and have continued intermittently since, gradually revealing the basilica’s foundations and plan. Today, you can walk among reconstructed columns that suggest the building’s former grandeur, trace the outline of the cruciform plan, and see the remains of the baptistery.

–

The site where John’s tomb once lay is marked and remains the emotional centre of the ruins. Some columns have been re-erected to help visitors visualise the original structure, and informational plaques explain the building’s history and significance.

The ruins are open to tourists and remain a destination for both history enthusiasts and Christian pilgrims, though on a much smaller scale than in medieval times. The site offers spectacular views over Selçuk and toward the ruins of ancient Ephesus, creating a powerful connection between these two great centres of early Christianity.

Above the basilica ruins stands the Isabey Mosque, built in 1375, and the Byzantine fortress of Ayasuluk, reminders of the layers of history that have unfolded on this strategic hill. Together, these monuments tell a story of religious transformation, architectural ambition, and the enduring power of sacred places to draw people across centuries and continents.

Leave a Reply