The movie theatre is more than just a room with a screen. At its best, it is a portal to other worlds, a cathedral of dreams, and an architectural statement about cinema’s cultural importance. From opulent picture palaces to modernist temples of film, the buildings where we watch movies have shaped how we experience them and reflect the evolving relationship between cinema and society.

The Nickelodeons: Cinema’s Humble Beginnings

The first dedicated film venues were modest affairs. In the early 1900s, entrepreneurs converted storefronts into “nickelodeons”, small theatres charging five cents admission. These bare-bones spaces seated a hundred people on wooden chairs or benches, with a projector at the back and a white sheet or painted wall serving as a screen. Nickelodeons were purely functional, designed to maximise profit from working-class audiences seeking cheap entertainment.

These storefront theatres proliferated rapidly. By 1910, an estimated 10,000 nickelodeons operated across America, concentrated in working-class neighbourhoods and immigrant communities. The architecture was negligible; what mattered was access and affordability. Operators decorated entrances with electric lights to attract attention, but interiors remained utilitarian. The experience was communal and sometimes chaotic, with live musical accompaniment, audience noise, and films changed several times daily to keep patrons returning.

Nickelodeons democratised entertainment but also concerned social reformers who worried about unsupervised minors, dark spaces facilitating immoral behaviour, and fire hazards in cramped wooden buildings. These concerns, combined with cinema’s growing respectability and profitability, would transform movie theatre design within a decade.

The Picture Palace Era: Architecture as Spectacle

As films grew longer and more sophisticated, exhibitors recognised that theatres themselves could enhance the experience and attract middle-class audiences. Between approximately 1910 and 1930, the “picture palace” emerged, theatres designed to make moviegoing itself an event worthy of the finest entertainment.

The Strand Theatre, New York City

The Strand Theatre, which opened on Broadway in 1914, pioneered the picture palace concept and deserves recognition as the first true movie cathedral. Designed by Thomas W. Lamb, an architect who would create dozens of theatres, The Strand seated 3,300 patrons in a space that rivalled legitimate theatres in elegance and comfort. The exterior featured a Classical Revival façade with columns and ornate detailing, while the interior boasted crystal chandeliers, plush seating, thick carpeting, and elaborate plasterwork.

What made The Strand revolutionary was not just its size and luxury but its statement that cinema deserved the same architectural respect as opera or theatre. Owner Samuel “Roxy” Roth Apfel employed a uniformed staff, installed air conditioning, and presented films with orchestral accompaniment. The theatre’s success demonstrated that audiences would pay premium prices for premium presentation, and every major city soon sought its own picture palace.

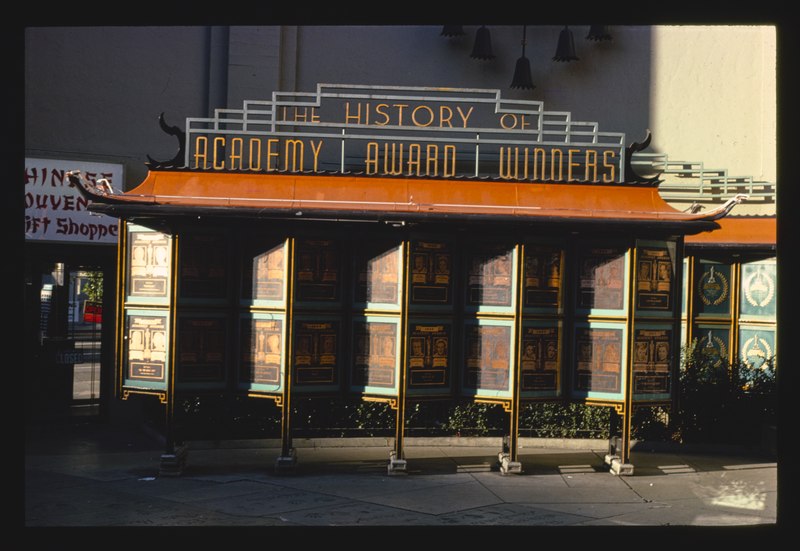

Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, Hollywood

When Sid Grauman opened his Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard in 1927, he created not just a movie house but a landmark that would become synonymous with Hollywood glamour. Architect Raymond M. Kennedy designed the theatre in an exotic Chinese style, though the architectural accuracy mattered less than creating a fantastical environment that transported patrons beyond ordinary life.

The exterior features a grand pagoda-style entrance with green copper roof, stone guardian lions, and coral-red columns. The forecourt, where celebrities began leaving handprints and footprints in cement shortly after opening, became Hollywood’s most famous sidewalk. The interior continues the Chinese motifs with elaborate decorative elements, though incorporating them loosely rather than authentically. The auditorium seats nearly 1,000 and features a grand proscenium arch and ornate details throughout.

Grauman’s Chinese Theatre hosted countless premieres and remains in operation today, a testament to its architectural durability and cultural significance. The theatre represents picture palace design at its most imaginative, where historical accuracy yielded to creating an immersive fantasy environment. Moviegoers were not just watching exotic stories; they were entering an exotic space that began the escapist experience before the film even started.

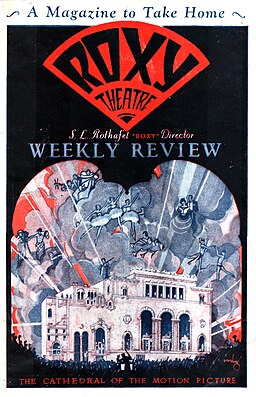

The Roxy Theatre, New York City

Samuel Rothapfel, having pioneered the palace concept with The Strand, opened his ultimate achievement in 1927. The Roxy Theatre, designed by Walter Ahlschlager, was billed as the “Cathedral of the Motion Picture” and seated an astonishing 5,920 patrons across multiple levels. The six-story lobby featured a grand staircase, marble columns, and tapestries. The auditorium itself resembled a Renaissance palace, with elaborate plasterwork, a mighty Wurlitzer organ, and a stage capable of hosting full theatrical productions.

The Roxy represented the picture palace at its zenith, massive, luxurious, and declaring that cinema had achieved art form status deserving of architectural monuments. The building cost $10 million, an enormous sum in 1927, and employed a staff of hundreds. Sadly, the Roxy was demolished in 1960 to make way for an office building, but its twenty-eight years of operation defined the picture palace ideal.

The Atmospheric Theatre: Creating Illusion

Architect John Eberson pioneered a distinct picture palace variant called the “atmospheric theatre.” Rather than mimicking opera houses or palaces, atmospheric theatres created the illusion of outdoor environments, typically Mediterranean courtyards, Spanish villages, or exotic gardens. The ceilings were painted deep blue with twinkling stars created by lighting effects and projected clouds. The walls featured elaborate three-dimensional plasterwork creating balconies, windows, and architectural details suggesting buildings surrounding a courtyard.

The Majestic Theatre, Houston, opened in 1923, exemplifying Eberson’s vision. The auditorium resembled an Italian garden at twilight, with false building façades along the walls, statuary, and a ceiling transformed into the night sky. The effect was remarkably convincing, especially in the era before sophisticated lighting and air conditioning made audiences constantly aware they were in an enclosed space.

Eberson designed hundreds of atmospheric theatres across America, each creating its own fantasy environment. The Paradise Theatre in Chicago evoked an Italian villa’s courtyard. The Tampa Theatre in Florida created a Mediterranean courtyard complete with false windows glowing as if with interior light. These theatres recognised that architecture could enhance cinema’s transportive power, quite literally taking audiences out of their everyday environment before the film began.

Art Deco Cinemas: Modernism Meets the Movies

As the 1920s progressed into the 1930s, architectural fashion shifted from historical revival styles toward Art Deco and Streamline Moderne. These modern styles emphasised geometric forms, streamlined curves, chrome and glass materials, and decorative elements drawn from industrial design rather than historical architecture.

The Odeon Cinemas, United Kingdom

Oscar Deutsch founded the Odeon cinema chain in Britain in 1930, and his theatres became synonymous with Art Deco cinema design. Deutsch hired architect Harry Weedon, who developed a distinctive house style that made Odeon theatres instantly recognisable. The typical Odeon featured a curved cream or white façade with horizontal bands of black tiles, a tall vertical tower bearing the Odeon name in large letters and streamlined curves suggesting speed and modernity.

The interiors matched the exterior modernism with chrome railings, geometric light fixtures, and stylised decorative elements. These theatres rejected historical nostalgia, instead embracing contemporary design that suggested cinema was a modern art form for the modern age. The Odeon Leicester Square, opened in 1937, became London’s premier venue and hosted countless royal premieres and major film debuts.

Deutsch’s vision of standardised yet distinctive modern cinemas influenced theatre design globally. The Odeon aesthetics, sleek, modern, and optimistic, captured 1930s and 1940s sensibilities perfectly. While later decades saw many Odeon theatres demolished or subdivided, those that survive are now protected as important examples of Art Deco architecture.

Radio City Music Hall, New York City

Though designed primarily as a variety theatre, Radio City Music Hall, which opened in Rockefeller Centre in 1932, represents Art Deco theatre architecture at its most spectacular. Architect Edward Durell Stone and designer Donald Deskey created an enormous auditorium seating 6,000 with a vast proscenium arch suggesting a sunset. The interior features murals, geometric light fixtures, and luxurious materials throughout.

The Grand Foyer features a sweeping staircase, gold-leaf ceiling, and mirrors creating infinite space. Every detail, from door handles to bathroom fixtures, received careful design attention. Radio City Music Hall has hosted film premieres, concerts, and its famous Christmas Spectacular, and remains in operation as both a landmark and a functioning entertainment venue.

Movie Palaces Around the World

While America pioneered picture palace architecture, the concept spread internationally, with each country adapting the design to local tastes and contexts.

Le Grand Rex, Paris

Opened in 1932, Le Grand Rex remains Europe’s largest cinema with 2,800 seats in its main auditorium. Architect Auguste Bluysen created an Art Deco masterpiece with the atmospheric theatre concept; – the auditorium ceiling depicts a Mediterranean night sky with stars and moving clouds. The interior suggests a Spanish-Moorish courtyard with false building façades and elaborate decorative elements.

The exterior features a distinctive curved façade with a tall tower and the theatre’s name in large, illuminated letters. Le Grand Rex became Paris’s premier cinema, hosting major film debuts and continuing to operate as a leading venue. The building represents how picture palace design translated across cultures, adapting American concepts to European sensibilities.

Capitol Theatre, Melbourne

Australia’s picture palaces rivalled their American counterparts in ambition. The Capitol Theatre, designed by architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin and opened in Melbourne in 1924, features one of the world’s most unusual theatre ceilings, a crystalline form suggesting a stalactite cave. The Griffins, better known for designing Canberra, created a unique vision combining geometric forms with naturalistic inspiration.

The auditorium’s ceiling remains one of the most photographed theatre interiors globally, its intricate plasterwork creating three-dimensional depth and pattern. The Capitol faced closure multiple times but was saved by heritage advocates and restored to operation, demonstrating increasing recognition of historic theatres’ cultural value.

The Regent Theatre, Melbourne

Also in Melbourne, the Regent Theatre opened in 1929 as one of the most elaborate picture palaces outside America. The interior replicated a European palace’s grand ballroom, with crystal chandeliers, ornate plasterwork, and rich decorative painting. The theatre cost an enormous sum and represented Australian cinema’s golden age confidence.

After decades of decay and closure, The Regent underwent comprehensive restoration in the 1990s, reopening as a venue for both films and live theatre. The restoration demonstrates the technical challenges of preserving these elaborate buildings, matching historical materials, recreating lost decorative elements, and updating technical systems while maintaining architectural integrity.

The Decline of the Picture Palace

The Depression and World War II slowed picture palace construction, and postwar changes made their operating model unsustainable. Television kept audiences’ home, suburban sprawl drew patrons away from downtown theatres, and operating costs for enormous buildings with large staffs became prohibitive. Many picture palaces closed, were demolished, or converted to other uses through the 1950s and 1960s.

The multiplex concept, pioneered in the 1960s, divided single large auditoriums into multiple smaller screens, maximising programming flexibility and revenue per square foot. This economic logic led many surviving picture palaces to be subdivided, their grand auditoriums partitioned into boxy screening rooms that destroyed their architectural integrity.

Preservation Efforts

By the 1970s, preservationists recognised that historic theatres were disappearing at an alarming rate. Organisations formed to advocate for their protection, arguing these buildings represented significant architectural and cultural heritage. Success came gradually, some theatres were saved through designation as historic landmarks, others found new life as performing arts centres, and some continued operating as cinemas, often supported by nonprofit organisations or specialty programming. –

The Castro Theatre in San Francisco, which opened in 1922, became a model for successful preservation. This Spanish Colonial Revival palace, designed by Timothy L. Pflueger, retains its original auditorium and continues to show films, with its mighty Wurlitzer organ providing intermission entertainment. The theatre serves as a community gathering place and tourist attraction while remaining financially viable through diverse programming.

Modernist Cinemas: Function Over Fantasy

As post-war architecture embraced International Style modernism, some new cinemas rejected historical pastiche for clean geometric forms and honest materials. These buildings made different architectural statements about cinema, not as escapist fantasy but as contemporary art deserving contemporary architecture.

*

*

Cinerama Dome, Los Angeles

The Cinerama Dome, opened in 1963, represents mid-century modern theatre architecture. Architect Welton Becket designed a distinctive geodesic dome to house the massive, curved screen required for the Cinerama widescreen process. The concrete dome structure, inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s designs, created the necessary unobstructed sightlines while making a bold architectural statement.

The building’s exterior is purely functional, a simple dome rising from a commercial boulevard, yet distinctive and memorable. The interior likewise prioritised optimal viewing geometry over decorative excess. The Cinerama Dome influenced subsequent purpose-built cinemas designed around specific projection technologies, proving that functional requirements could generate interesting architecture.

The theatre survived various economic challenges and was incorporated into the larger ArcLight Hollywood complex in 2002, with the dome preserved as the centrepiece. * It continues operating, showing mainstream releases and special presentations that take advantage of its unique screen.

National Film Theatre, London

The National Film Theatre, built on the South Bank in 1957 and later expanded, took a different modernist approach. Rather than creating a monumental building, the NFT (now called BFI Southbank) was designed as part of the Festival of Britain’s cultural infrastructure. The building’s brutalist concrete construction reflected the period’s architectural values, honesty of materials, functional clarity, and democratic accessibility.

The NFT’s interiors prioritised excellent sightlines and acoustics over decorative flourishes. This no-nonsense approach suited the venue’s mission as a repertory cinema showing classics, international films, and experimental works for serious film audiences. The building underwent renovation in 2007 but maintained its essential character, demonstrating that even austere modernist architecture can become beloved landmarks.

Multiplexes and Megaplexes: The Contemporary Landscape

From the 1970s onward, most new cinema construction followed the multiplex model, multiple small auditoriums sharing lobby, concession, and projection facilities. These theatres, typically in suburban shopping centres or standalone complexes, prioritised economic efficiency over architectural distinction. The multiplex architecture was usually a generic, commercial building design with little reference to cinema’s cultural significance.

The megaplex variant, pioneered in the 1990s, expanded the concept to 16, 20, or even thirty screens. These massive entertainment complexes incorporated restaurants, games, and other attractions, creating destinations rather than simple movie theatres. The architecture often borrowed from retail design, bright, clean, and comfortable, but rarely distinctive or memorable.

Some contemporary theatre chains have attempted to differentiate through upscale experiences, luxury seating, premium food and beverage service, and more sophisticated interior design. Alamo Drafthouse, iPic, and similar chains target audiences willing to pay premium prices for enhanced comfort and service, though their architecture remains conventional.

IMAX and Specialty Formats: Form Following Technology

The development of large-format systems like IMAX created new architectural requirements. IMAX theatres require enormous screens, steeply raked seating, and specific geometric relationships between screen, seats, and projection systems. These technical demands generate distinctive interior spaces, though they are usually housed within conventional building exteriors.

Some IMAX venues achieved architectural distinction. The IMAX theatre at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, opened in 1976, integrated the giant screen into a building designed by architect Gyo Obata to house aviation and space artifacts. The theatre’s presence influenced the building’s overall design, creating visual and functional relationships between the exhibits and the cinema.

The Revival of Cinema Architecture

Recent decades have seen renewed interest in cinema architecture, both through the preservation of historic theatres and the creation of distinctive new venues.

Cinema Pathé Tuschinski, Amsterdam

The Tuschinski Theatre, opened in 1921, survived decades of neglect and insensitive alterations before a comprehensive restoration beginning in 1998. Abraham Tuschinski, a Polish Jewish immigrant, commissioned architects Hijman Louis de Jong and Jaap Gidding to create an opulent cinema combining Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Amsterdam School styles. The result is an ornate fantasy featuring elaborate decorative elements, luxurious materials, and distinctive architectural features throughout.

The theatre’s preservation and restoration demonstrate growing recognition of cinema architecture’s cultural value. Rather than simply maintaining the building, the restoration sought to recreate the original experience while updating technical systems. The Tuschinski now operates as a first-run cinema showing mainstream films in a historic setting, proving that preservation and commercial viability can coexist.

Fox Theatre, Atlanta

The Fox Theatre, opened in 1929 as a Shriners’ temple and movie palace, exemplifies successful adaptive reuse. This elaborate Moorish-style building, designed by architects Olivier Vinour and Marye, Alger & Vinour, faced demolition in the 1970s but was saved by community advocacy. Today it operates as a performing arts centre and occasional film venue, its elaborate Arabian Nights interior and atmospheric ceiling preserved and maintained.

The Fox’s survival depended on finding economically sustainable uses beyond just showing films. By hosting concerts, Broadway tours, and special events, the theatre generates revenue while maintaining its architectural integrity. This mixed-use model has proven successful for numerous historic theatres that could not survive on film exhibition alone.

Contemporary Cinema Design

Some recent cinema projects have pursued architectural distinction, recognising that distinctive buildings can differentiate theatres in a competitive entertainment landscape.

The Cornerhouse, Manchester (now HOME)

When Manchester’s Cornerhouse arts cinema relocated to a new building in 2015, architects Meccano created a contemporary structure housing cinemas, theatres, and galleries under one roof. The building’s exterior features a distinctive perforated metal skin, while interiors provide flexible spaces for various media presentations. The architecture acknowledges cinema’s place within broader contemporary culture rather than treating it as a separate art form requiring specialised architecture.

Cinema at Westfield London

The Vue cinema at Westfield London shopping centre, opened in 2008, demonstrates how contemporary multiplexes can achieve architectural interest. The cinema occupies a distinctive curved structure within the larger shopping complex, with interiors featuring dramatic lighting and contemporary design. While still fundamentally a multiplex, the building recognises that cinema spaces can be both functional and aesthetically engaging.

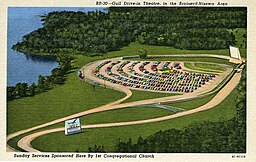

Drive-In Theatres: A Distinct Typology

No discussion of cinema architecture is complete without acknowledging drive-in theatres, a distinctly American building type that peaked in the 1950s and 1960s. Drive-ins required massive land areas for parking, with giant screens visible from hundreds of cars. The architecture was minimal: a projection booth, concession stand, and a playground, but the spatial planning created unique social environments where families could watch films from their cars.

Drive-ins declined dramatically as land values rose and suburban development consumed their large footprints. Those that survive often operate seasonally or have found niche audiences valuing the nostalgic experience. Some operate as heritage attractions, preserving a vanished piece of American popular culture.

The Future of Cinema Architecture

As streaming services challenge theatrical exhibition, questions arise about cinema buildings. Some predict the death of movie theatres, while others argue that theatrical experiences will survive by offering something streaming cannot: communal viewing in spaces designed specifically for cinema.

Historic theatres increasingly emphasise their architectural and cultural significance alongside their function. Showing films becomes one activity among many, concerts, lectures, and special events, which justify maintaining these buildings. The architecture itself becomes part of the attraction, with tours, events, and heritage tourism generating revenue beyond ticket sales.

New cinema construction faces uncertain economics. The multiplex model appears exhausted, lacking architectural distinction or experiential advantages over home viewing. Some predict future cinemas will be smaller, more specialised venues emphasising quality over quantity, returning in some ways to cinema’s art-house roots.

Conclusion: Architecture and Experience

Cinema architecture matters because buildings shape experiences. The picture palace’s ornate lobbies and grand auditoriums declared that watching films was special, deserving of architectural ceremony. The multiplex’s efficient blandness treats cinema as commodity consumption. The art house’s intimate scale creates different viewing communities than the megaplex’s anonymous crowds.

The greatest cinemas, Grauman’s Chinese, The Grand Rex, the Tuschinski, Radio City Music Hall, endure because their architecture adds something irreplaceable to the experience. These buildings make moviegoing into an event, a ritual, a moment of entering a space dedicated to imagination and storytelling. As cinema evolves technologically and culturally, these architectural monuments remind us that where we watch films matters as much as what we watch, and that the movie palace’s dream of creating temples worthy of cinema’s magic remains relevant even in our digital age.

Book Suggestions

| Title | Cinema Architecture |

| Author | Chris van Uffelen |

| Publisher | Braun Publishing AG / 2009 |

| Pages | 256 |

| Format | Hardback |

| Available from | Bookshop.org Click Here |

| Waterstones | |

| Title | Cinemas in Britain: One Hundred Years of Cinema Architecture |

| Author | Various |

| Publisher | Often reprinted; title varies by edition) |

| Pages | varies |

| Formats | Hardback |

| Paperback | |

| Available from | Amazon Click Here (2010 hardback version) |

| Bookshop.org Click Here (paperback version) | |

| Title | Cinematic Style: Fashion, Architecture and Interior Design on Film |

| Author | Jess Berry |

| Publisher | Bloomsbury Visual Arts / 2022 |

| Pages | 224 |

| Format | Hardback |

| Ebook | Kindle Click Here |

| Available from | Waterstones |

| Amazon Click Here (paperback) | |

| Click Here (hardback) | |

| Title | Atmosphere, Architecture, Cinema: Thematic Reflections on Ambiance and Place |

| Author | Michael Tawa |

| Publisher | Springer Nature / 2022 |

| Pages | 284 |

| Formats | Hardback |

| Paperback | |

| Ebook | Kindle https://amzn.to/48Wm5cA |

| Available from | Amazon https://amzn.to/4bbrYE9 |

| Bookshop.org Click Here (Paperback)

Click Here (Hardback) |

|

| Title | Organic Cinema: Film, Architecture, and the Work of Béla Tarr |

| Author | Thorsten Botz-Bornstein |

| Publisher | Berghahn Books / 2021 |

| Pages | 238 |

| Formats | Paperback |

| Available from | Amazon Click Here |

| Bookshop.org Click Here | |

| Title | Architecture, Film, and the In‑between: Spatio‑cinematic Betwixt |

| Author | Various |

| Publisher | Various |

| Pages | Various |

| Physical | Paperback |

| Available from | Amazon Click Here (paperback)

Click Here (hardback) |

| Title | The Architecture of the Screen: Essays in Cinematographic Space |

| Author | Graham Cairns |

| Publisher | Intellect |

| Pages | 360 |

| Format | Paperback |

| Available from | Amazon Click Here |

| Waterstones | |

| Title | Architecture, Philosophy and the Pedagogy of Cinema: From Benjamin to Badiou |

| Author | Various |

| Publisher | Routledge |

| Pages | 168 |

| Format | Paperback |

| Ereader |

Kindle Click Here |

| Hardback | |

| Available from | Amazon Click Here(hardback) |

| Bookshop.org |

Leave a Reply