The ancient city of Ephesus, once a bustling Roman port on the western coast of what is now Turkey, holds a unique place in Christian history as the city where Mary, the mother of Jesus, is believed to have spent her final years. This tradition, though debated by scholars and theologians for centuries, has made Ephesus a major pilgrimage site and a focal point for Marian devotion. The story of Mary in Ephesus interweaves biblical interpretation, early church tradition, mystical visions, and archaeological discovery into a narrative that continues to inspire millions of believers around the world.

The Biblical Foundation

The connection between Mary and Ephesus begins at the foot of the cross. According to the Gospel of John, as Jesus was dying, he looked down at his mother Mary and his beloved disciple John standing nearby. In a profound act of love and care, Jesus said to Mary, “Woman, here is your son,” and to John, “Here is your mother.” From that moment, John took Mary into his home.

This brief passage provides the foundation for the tradition that Mary went to live with John after Jesus’ crucifixion. But why would they have gone to Ephesus? The answer lies in the dangerous situation facing early Christians in Jerusalem.

Following Jesus’ death, his disciples faced persecution in Jerusalem, causing them to scatter around the Mediterranean world. For Mary, the mother of a man executed as a political criminal claiming to be the “King of the Jews,” remaining in Jerusalem would have been particularly perilous.

Why Ephesus?

Ephesus was a major commercial centre with an international trade port located by the Aegean Sea, connecting East and West through both maritime routes and the Royal Road that began in Persia. The city’s strategic location made it an ideal base for spreading Christianity beyond Judea. As one of the great cosmopolitan cities of the Roman Empire, Ephesus offered both relative safety from the immediate dangers of Jerusalem and opportunities for the new Christian community to take root.

The city also had a fascinating spiritual history. For centuries before Christianity arrived, Ephesus had been a centre for the worship of female deities. Local Anatolian tribes worshipped the mother goddess Cybele, who was later merged with the Greek goddess Artemis. The magnificent Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, drew pilgrims from across the Mediterranean. Some scholars suggest this long tradition of venerating divine femininity may have made Ephesus particularly receptive to honouring Mary as the mother of God.

Early Historical Evidence

The earliest written references to Mary’s presence in Ephesus are frustratingly vague and appear centuries after the events they describe. The first mention appears in the synodal letter of the Council of Ephesus in 431, which refers to “the city of the Ephesians, where John the Theologian and the Virgin Mother of God St. Mary lived and are buried”. However, this statement is ambiguous and may have been influenced by the council’s political and theological purposes rather than historical certainty.

More concrete evidence exists for John’s presence in Ephesus. Polycrates, the bishop of Ephesus in the 2nd century, wrote in a letter that John was buried in Ephesus, and early church historian Eusebius recorded that after persecution began in Jerusalem, the apostles scattered around the Mediterranean, with John coming to Ephesus. The Basilica of St. John, constructed in the 6th century by Emperor Justinian I over what was believed to be John’s tomb, still stands near Ephesus as testimony to this tradition.

If John truly settled in Ephesus, the logic follows that he would have brought Mary with him, as Jesus had entrusted her to his care. Yet the evidence remains circumstantial rather than definitive.

The House on the Mountain

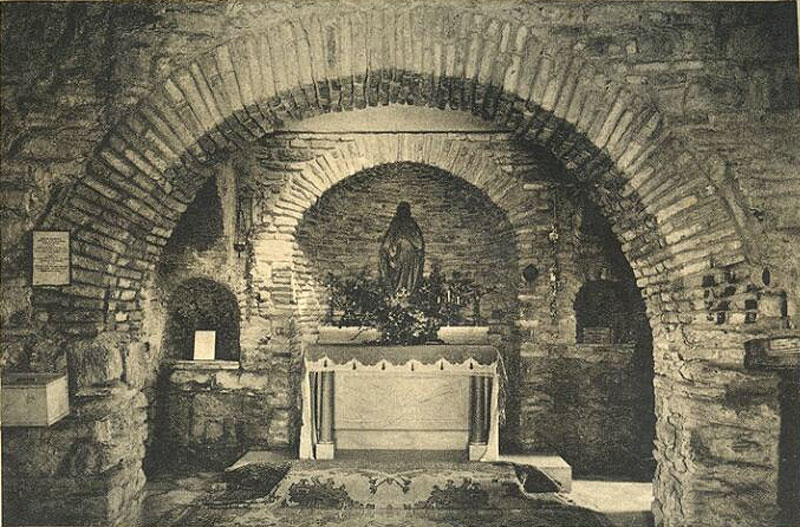

The most tangible connection between Mary and Ephesus is a small stone house located on Mount Koressos (known in Turkish as Bülbüldağı, or “Mount Nightingale”), about five kilometres from the ancient city. This site was discovered in the 19th century following descriptions from the visions of Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich, a German Augustinian nun who never left her homeland but reported detailed visions of Mary’s final home.

Anne Catherine Emmerich was a bedridden mystic in the town of Dülmen, Germany, who from 1802 until her death in 1824 experienced elaborate visions of biblical events. Her secretary, the poet Clemens Brentano, recorded her accounts in a book published in 1833 titled “The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ.” Emmerich described the location with remarkable specificity: Mary did not live in Ephesus itself, but in the countryside near it, in a dwelling on a hill to the left of the road from Jerusalem, approximately three and a half hours from Ephesus.

For nearly fifty years, Emmerich’s visions were treated as interesting spiritual literature but not taken as literal geographical directions. Then, on 18th October 1881, a French priest named Abbé Julien Gouyet discovered a small stone building on a mountain overlooking the Aegean Sea and the ruins of ancient Ephesus, matching Emmerich’s descriptions. Initially, his claims were dismissed by most authorities.

The true breakthrough came a decade later. On 29th July 1891, urged by Sister Marie de Mandat-Grancey, two Lazarist missionaries from Smyrna, Father Poulin and Father Jung, rediscovered the building using Emmerich’s descriptions as their guide. Crucially, they learned that the local villagers from Şirince, descendants of early Christians, had long venerated this roofless ruin and made pilgrimages there, particularly to celebrate the Dormition of the Virgin Mary. This suggested the site had been honoured for generations, independent of Emmerich’s visions.

Sister Marie de Mandat-Grancey dedicated the rest of her life to preserving the site. She acquired the land, oversaw restoration work, and established the house as a place of pilgrimage. The restored portions were carefully distinguished from the original structure with a red painted line, allowing visitors to see which elements were ancient and which were modern additions.

Church Recognition and Papal Visits

While the Catholic Church has never officially confirmed the site’s authenticity, in 1896 Pope Leo XIII formally recognised Mary’s House in Ephesus as an official place of pilgrimage. His successor, Pope Pius X, granted a plenary indulgence to pilgrims who visited the shrine. These actions gave the site significant legitimacy within Catholic tradition, even without declaring it definitively authentic.

The site’s importance grew dramatically through papal visits. Pope Paul VI became the first pope to visit in 1967, bringing a bronze lamp as a gift for the “Blessed Virgin.” Pope John Paul II visited in 1979 and celebrated an outdoor mass for thousands of pilgrims. Pope Benedict XVI also made the pilgrimage in 2006. These visits by the Church’s highest authority dramatically increased the shrine’s visibility and cemented its place as a major destination for Catholic pilgrims worldwide.

Today, the house operates as a functioning chapel. Every 15th August, a High Mass is held there to celebrate the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and daily masses are offered throughout the year. The site attracts not only Catholics but also Orthodox Christians and even Muslim visitors, as Islamic tradition holds Mary in high honour as the mother of the Prophet Jesus.

A Place of Prayer and Petition

One of the most touching aspects of the shrine is the thousands upon thousands of scraps of paper tucked into a wall beside the house, written petitions for intercessions for health, help with exams, troubled children, and a litany of other needs. This “wishing wall” has become a powerful symbol of the continuing connection believers feel with Mary. Pilgrims from every corner of the globe leave their prayers, hopes, and heartaches written on pieces of paper, fabric, or whatever material is at hand, trusting that Mary will carry their petitions to her son.

The house itself is modest, consisting of just a few small rooms. Unlike the grandeur of the ancient Temple of Artemis that once dominated Ephesus, Mary’s house is humble and unpretentious. For many visitors, this simplicity feels appropriate, a quiet refuge where an elderly woman lived out her final years in contemplation and prayer, far from the political intrigues and dangers of Jerusalem.

The Council of Ephesus: Mary as Theotokos

Mary’s association with Ephesus gained theological significance in 431 AD when the city hosted one of Christianity’s most important ecumenical councils. The Council of Ephesus was convened by Roman Emperor Theodosius II to resolve a fierce controversy about Mary’s proper title and, more fundamentally, about the nature of Christ himself.

The dispute centred on Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, who objected to calling Mary “Theotokos” (God-bearer or Mother of God). Nestorius argued that Mary gave birth to Christ’s human nature, not to God himself, and therefore should be called “Christotokos” (Christ-bearer) rather than Theotokos. His opponent, Cyril of Alexandria, insisted that because Christ was one unified person, both fully divine and fully human, Mary could rightly be called the Mother of God.

The theological stakes were enormous. The question wasn’t really about Mary but about Christ: Was Jesus one unified person, or were his divine and human natures so separate that he was essentially two different beings? If Mary only gave birth to Jesus’ human nature, and that nature was somehow separate from his divinity, then the incarnation, God becoming human, would be called into question.

The Council met from 22nd June to 31st July 431, at the Church of Mary in Ephesus. The choice of venue was significant; Ephesus was known as a centre of Marian devotion, and the council met in a church dedicated to her. The proceedings were contentious and politically charged. Cyril opened the council before all the bishops had arrived, and Nestorius, sensing he was outnumbered, refused to attend. The council condemned Nestorius as a heretic and affirmed that Mary should indeed be called Theotokos.

The Council declared that Jesus was one person with both human and divine natures intimately and hypostatically united, and therefore the Virgin Mary was rightly called Theotokos because she gave birth to God become flesh. This decision had profound implications not only for theology but for Marian devotion. By affirming Mary as the Mother of God, the Council elevated her status in Christian worship and piety.

The Council of Ephesus thus created a unique convergence: Ephesus became associated with Mary both through the tradition of her physical presence there and through the theological affirmation of her most exalted title. For believers, this seemed providential, that the city where Mary allegedly lived her final days would become the site where the Church definitively proclaimed her as Theotokos.

The Church of Mary

Beyond the house on Mount Koressos, another important Marian site exists within the ancient city of Ephesus itself. The Church of the Virgin Mary, erected in the 3rd century within an earlier building, was the first church dedicated to the mother of Christ and the most significant Christian structure in Ephesus. This church, where the Council of Ephesus convened, replaced earlier pagan structures dedicated to female deities.

The church was built inside the southern portico of the Olympian, which had been erected around 130 AD as a temple for the Imperial Cult of Emperor Hadrian as Zeus Olympios. This transformation from pagan temple to Christian church symbolised the religious revolution sweeping through the Roman Empire. The fact that this church was dedicated to Mary, rather than to one of the apostles or martyrs, reflects the deep association between Mary and Ephesus that already existed in the early Christian consciousness.

Scholarly Scepticism and Competing Traditions

Despite the devotion surrounding Mary’s connection to Ephesus, scholars have raised significant doubts. Some critics note that the tradition of Mary’s association with Ephesus only arose in the twelfth century, relatively late in Christian history. Before that period, Jerusalem held the stronger claim as the location of Mary’s final days and death.

The Church of the Dormition on Mount Zion in Jerusalem represents an alternative tradition. Many early sources suggest Mary never left Jerusalem, instead remaining with the apostolic community there. The Jerusalem tradition has the advantage of greater antiquity and may seem more plausible. Why would an elderly woman undertake a dangerous journey of over 600 miles to a foreign city when she had family and community support in Jerusalem?

The evidence for Ephesus rests primarily on later traditions, John’s documented presence in the city, and the continuous veneration of the house site by local Christians. However, these factors could be explained in other ways. Local Christians may have venerated the site for reasons unrelated to Mary, or a pious tradition may have developed over time that conflated different historical facts.

The discovery of the house following Emmerich’s visions adds another layer of complexity. Sceptics point out that Brentano’s account of Emmerich’s visions was published posthumously and may have been embellished. Furthermore, the fact that a structure matching her descriptions was found could be coincidental, ruins of ancient houses were common throughout the region. The practice of interpreting such discoveries through the lens of religious expectation was not unusual in the 19th century.

A Matter of Faith

Ultimately, the question of whether Mary truly lived in Ephesus may be less important than what the tradition represents to believers. While there is no direct biblical evidence or conclusive archaeological findings to confirm Mary’s presence in Ephesus, the tradition has been passed down through generations and remains a matter of faith and interpretation for different Christian denominations.

For pilgrims who climb the winding path to the house on Mount Koressos, the experience transcends historical verification. They come to connect with the mother of Jesus in a place of peace and beauty, to pray for her intercession, and to reflect on her role in the story of salvation. Whether or not Mary’s physical presence once sanctified this spot, her spiritual presence is palpable to those who seek it there.

The site also represents something broader, the human need to connect abstract faith with concrete places. Throughout Christian history, pilgrims have sought out locations associated with Jesus, Mary, and the saints, finding that physical journeys deepen spiritual understanding. The house at Ephesus serves this purpose beautifully: a modest dwelling in a serene setting, where visitors can imagine an elderly woman living out her final years in quiet contemplation, surrounded by a small Christian community that revered her as the mother of their Lord.

Interfaith Significance

Interestingly, Mary’s house has become a rare point of interfaith harmony. Muslims revere Mary (Maryam in Arabic) as the mother of the Prophet Jesus (Isa) and honour her as one of the most righteous women in history. The Quran affirms her virginal conception of Jesus and presents her as a model of faith and purity. Consequently, Muslim visitors often come to the shrine to pay their respects, creating a remarkable space where Christians and Muslims share devotion to the same holy figure.

This interfaith dimension adds another layer of meaning to Mary’s association with Ephesus. In a region that has witnessed centuries of religious conflict, the house on Mount Koressos stands as a quiet testimony to shared reverence and common spiritual heritage.

Conclusion: Legend, History, and Living Faith

The story of Mary in Ephesus occupies an ambiguous space between history and tradition, archaeology and mysticism, scepticism and faith. The evidence for her presence there is suggestive but not conclusive. The house discovered on Mount Koressos may or may not be her actual dwelling. The visions of a 19th-century German nun may or may not have been genuine revelations of historical truth.

Yet for millions of believers, these uncertainties do not diminish the site’s significance. The tradition of Mary in Ephesus has endured for centuries, sustained by continuous devotion and validated by papal recognition. Whether Mary actually lived in that small stone house matters less than what the house represents: a connection to the mother of Jesus, a place to bring prayers and petitions, a tangible link to the early Christian community, and a reminder of Mary’s faithful response to God’s call.

In the end, Mary of Ephesus embodies the mystery at the heart of religious faith, the interplay between the historical and the transcendent, between what can be proven and what can only be believed. As pilgrims continue to climb the mountain to visit the modest house, leaving their written prayers on the wall, they participate in a tradition that bridges centuries and continents, connecting them to the earliest Christians and to the humble Jewish woman who said “yes” to God and changed the course of human history.

Leave a Reply