Few stories have been adapted for film as many times as Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Since the dawn of cinema itself, filmmakers have returned again and again to Ebenezer Scrooge’s journey from miser to philanthropist, finding in it something eternally cinematic, ghosts and spectacle, darkness and redemption, social conscience and emotional catharsis. With estimates suggesting over 400 adaptations across film, television, and other media, A Christmas Carol holds a unique place in cinematic history. Yet among this vast library, certain versions stand out, not just for their faithfulness to Dickens or their technical achievements, but for their cultural impact and enduring place in our collective Christmas consciousness.

The Silent Era: Birth of a Cinematic Tradition (1901-1935)

The very first film adaptation appeared remarkably early in cinema’s history. Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost, released in November 1901, was a six-minute British silent film directed by Walter R. Booth and produced by early film pioneer Robert W. Paul. Created when filmmaking itself was still experimental, this pioneering effort faced the challenge of condensing Dickens’s 80-page tale into mere minutes of footage.

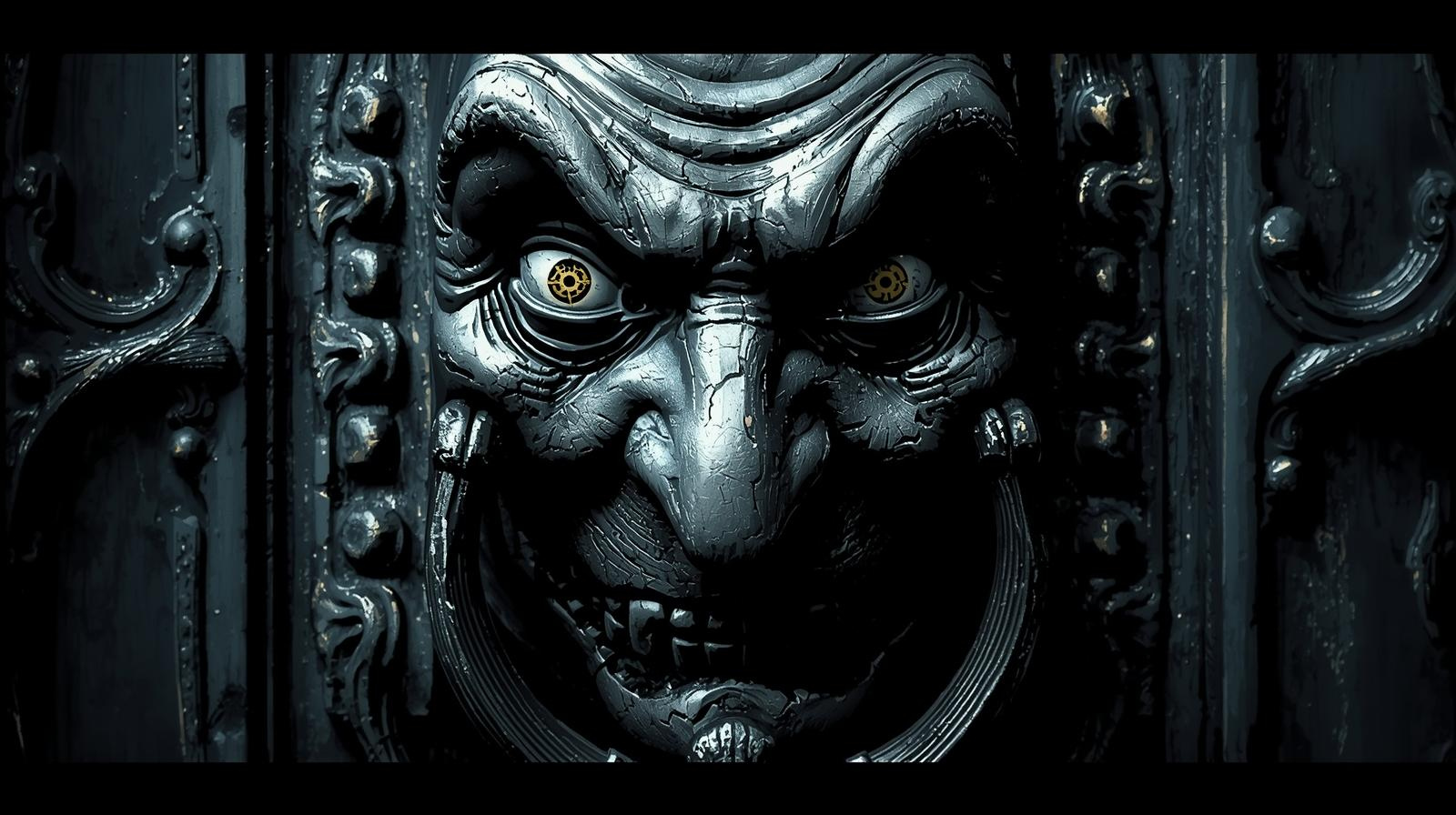

The film used trick photography, a specialty of both Booth and Paul, and featured superimposed images to show Marley’s face on the door knocker, one of the story’s most iconic moments. The film is also believed to feature the first use of intertitles on-screen, a milestone in film history. Today, only about three and a half minutes of this historic film survive, preserved by the British Film Institute.

The silent era saw numerous adaptations, each grappling with the same fundamental challenge: how to convey Dickens’s emotional and spiritual journey without dialogue. The best known silent adaptation was the 1913 version starring Seymour Hicks as the miserly curmudgeon, who would go on to make the role his own across thousands of stage performances and later reprising it in 1935 for the first “talkie” version of the story.

The Classic Era: Alastair Sim’s Definitive Scrooge (1951)

For many, the 1951 British production Scrooge (released in America as A Christmas Carol) represents the gold standard against which all others are measured. Directed by Brian Desmond Hurst with a screenplay by Noel Langley, this black-and-white masterpiece stars Alastair Sim in what has become the most celebrated interpretation of Ebenezer Scrooge.

Initially, the film didn’t find immediate acclaim. For decades it fell in the shadow of the 1938 version starring Reginald Owen. But through repeated television broadcasts, particularly during the Christmas season, the 1951 version gradually built a devoted following that eventually eclipsed all previous adaptations.

What makes Sim’s performance so enduring? Alastair Sim’s portrayal captures the complex dichotomy of the character, balancing both his cruel and empathetic sides. Unlike some interpretations that play Scrooge as a one-dimensional villain, Sim reveals the psychological complexity beneath the miserliness. He adds little touches to the character that sets his performance apart from the countless other Scrooges—the way he calculates every transaction, the momentary hesitations that reveal his suppressed humanity, the explosive joy of his final transformation.

The film’s technical achievements matched its performances. The stark black and white contrast, instead of making the film look dated, enhanced the cold misery and the horror in grand noir style. The atmospheric cinematography creates a Victorian London that feels both historically authentic and dreamlike, perfect for a ghost story.

The screenplay takes some liberties with Dickens’s original text, expanding backstory and adding scenes not in the novella. We see young Scrooge and his business partner Marley taking over their employer’s failing business, providing context for Scrooge’s transformation into a ruthless businessman. These additions, rather than betraying Dickens, deepen our understanding of how Scrooge became who he is.

Aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes gave the film an 86% “Fresh” rating based on 36 reviews, with the consensus reading “The 1951 adaptation of Charles Dickens’ timeless classic is perhaps the most faithful film version, and Alastair Sim’s performance as Scrooge is not to be missed”.

For generations raised on this version, no other Scrooge quite measures up. The film has never fallen out of circulation, airing reliably every December and available on virtually every home video format ever invented. Its influence on subsequent adaptations is immeasurable, countless actors playing Scrooge have consciously or unconsciously channelled elements of Sim’s interpretation.

Television Comes of Age: George C. Scott’s Dangerous Scrooge (1984)

The 1984 television film directed by Clive Donner and starring George C. Scott as Ebenezer Scrooge premiered on CBS on December 17, 1984, and quickly established itself as a rival to the 1951 classic. For viewers who grew up in the 1980s and beyond, Scott’s interpretation often supplants Sim’s as the definitive Scrooge.

What distinguishes Scott’s Scrooge is his physicality and menace. Tom Nichols of The Atlantic wrote in 2023, “There are some good adaptations of Charles Dickens’ classic A Christmas Carol, and many bad ones, but only one truly great version, and it is the 1984 made-for-television movie starring George C. Scott,” celebrating Scott’s portrayal of Scrooge as “a barrel-chested bully, an imposing and nasty piece of work”.

Where earlier Scrooges might be interpreted as simply greedy or cold, Scott’s Scrooge feels genuinely dangerous. He doesn’t just refuse charity, he seems capable of genuine cruelty. This makes his eventual transformation more powerful and less predictable. We’re not entirely certain he can be redeemed, which gives the story real dramatic tension.

The film was shot in the historic medieval county town of Shrewsbury in Shropshire, giving it an authenticity that studio-bound productions lack. The supporting cast reads like a who’s who of British acting talent: Frank Finlay as Marley’s ghost, David Warner as Bob Cratchit, Susannah York as Mrs. Cratchit, Angela Pleasence as the Ghost of Christmas Past, and Edward Woodward as a memorably robust Ghost of Christmas Present.

The production values were exceptional for a television movie. The film received positive reviews, with praise going to the sets, soundtrack, cinematography, and the performances of the cast, particularly Scott’s portrayal of Scrooge. Scott received an Emmy nomination for his performance, and the film helped revitalise his career, leading to a successful second act focused on television movies.

The film earned high Nielsen ratings, ranking 10th out of 65 shows airing the week of December 17-23, 1984, with a 20.7 household rating and a 30 percent audience share. Upon its UK premiere on November 18, 1984, the film drew an estimated audience of over 12 million viewers, remarkable for a single television broadcast in the pre-streaming era.

Unlike many made-for-TV movies that disappear after their initial broadcast, this A Christmas Carol has remained in continuous circulation, becoming a holiday staple on cable channels and streaming services. It occupies a unique space as both a television event and a film worthy of theatrical release (it played in cinemas in the UK).

The Modern Twist: Scrooged and Corporate Christmas (1988)

While most adaptations of A Christmas Carol maintain Dickens’s Victorian setting, 1988’s Scrooged dared to transplant the story to contemporary America, specifically, to the cutthroat world of 1980s network television. Directed by Richard Donner and starring Bill Murray as Frank Cross, a ruthless TV executive, the film uses Dickens’s framework to satirise modern media culture and the commercialisation of Christmas itself.

Murray plays Frank Cross, the ruthless and cynical president of IBC television, preoccupied with ensuring the success of his extravagant live broadcast of A Christmas Carol scheduled for Christmas Eve. The meta-textual irony, a modern Scrooge producing a broadcast of Dickens’s story even as he lives out his own version, provides much of the film’s satirical bite.

The film came at a pivotal moment in Murray’s career. Though it’s easy to remember the 1980s as a decade packed with Bill Murray comedies, Scrooged marked a re-emergence of sorts of the in-demand comedian after a four-year hiatus following Ghostbusters. Murray returned to acting seeking projects with more substance, and worked extensively with screenwriters Mitch Glazer and Michael O’Donoghue to reshape the script before agreeing to participate.

The film takes considerable liberties with Dickens’s story, updating not just the setting but the tone and themes. Frank’s detachment from traditional Christmas values is starkly highlighted in lines like “When I want a wife, I’m gonna buy one,” a statement that would have been startling even in Dickens’s 19th-century London, perfectly reflecting the 1980s obsession with commodification.

The ghosts receive radical reinterpretations. The Ghost of Christmas Present is rendered as a whimsical fairy inclined towards slapstick violence, humorously diverging from Dickens’s sombre depiction and embodying the late 80s’ flair for theatricality. Carol Kane’s manic, physically abusive Ghost of Christmas Present became one of the film’s most memorable elements, equal parts hilarious and unsettling.

Scrooged‘s reception was initially mixed. The film was met with a mixed response from critics who found the film either too mean-spirited or too sentimental. Roger Ebert, in a notably harsh review, found Murray’s performance too genuinely angry, lacking the self-mocking irony that usually made his rudeness entertaining. Yet test audiences loved it, and the film succeeded commercially, grossing over $100 million worldwide.

Time has been kind to Scrooged. Since its release, Scrooged has become a regular television Christmastime feature, with some critics calling it an alternative to traditional Christmas films, and others arguing that Scrooged was ahead of its time, making it relevant in the modern day. Modern retellings of A Christmas Carol shy away from tackling what selfish hoarding and toxic greed look like in today’s world, but Scrooged tackles that reality head-on.

The film’s final scene, where Murray’s redeemed Frank Cross crashes the live broadcast to deliver an impassioned speech about Christmas directly to the camera, remains controversial—some find it genuinely moving, others see it as awkward and overwrought. But it’s undeniably memorable, and the film’s closing singalong of “Put a Little Love in Your Heart” by Annie Lennox and Al Green became a Christmas staple in its own right.

The Muppets’ Masterpiece: Heart, Humour, and Faithfulness (1992)

In 1992, an unlikely candidate emerged as one of the most beloved, and, surprisingly, most faithful, adaptations of Dickens’s novella: The Muppet Christmas Carol. Directed by Brian Henson (Jim Henson’s son) in his feature directorial debut, the film faced scepticism. Could felt puppets do justice to Dickens? Would the Muppets’ trademark humour undermine the story’s emotional weight?

The answer, as it turned out, was a resounding yes on both counts.

Brian Henson and writer Jerry Juhl initially envisaged the project as a parody, with the Muppets as a Monty Python-style ensemble running riot through the story of Scrooge. But Henson had a better instinct: “I thought, what if we did it completely straight? What if the Muppets are just the characters, and we tell the story?” This decision proved inspired.

The film’s secret weapon is Michael Caine as Ebenezer Scrooge. Michael Caine’s performance as Scrooge easily surpasses those of Reginald Owen (1938), George C. Scott (1984) and Patrick Stewart (2001), with a more genuine degree of transformation and redemption in his characterisation. Caine made a crucial decision: he would play Scrooge absolutely straight, treating his Muppet co-stars as if they were accomplished human actors. No winking at the camera, no acknowledging the absurdity of acting opposite puppets.

The casting of Muppet characters in Dickensian roles works brilliantly. Kermit the Frog as the long-suffering Bob Cratchit, Miss Piggy as his fierce but loving wife, and Robin the Frog as Tiny Tim all feel natural. Statler and Waldorf, the Muppet Show’s heckling balcony critics, make perfect Jacob and Robert Marley (yes, the film adds a second Marley brother to accommodate both hecklers).

Perhaps most ingenious is casting Gonzo as Charles Dickens himself, with Rizzo the Rat as his companion. According to Brian Henson, 95% of what Gonzo says in the movie is taken directly from Dickens’s original text. By having Gonzo narrate using Dickens’s actual prose, the film maintains a connection to the source material that many “serious” adaptations abandon. This allows the film to have its Muppet cake and eat Dickens too, authentic Victorian dialogue exists alongside Rizzo asking “Is this boring?” and noting they’re at the scary part where he “should have known there’d be more songs.”

The film was the first Muppet film to be produced following the deaths of creator Jim Henson and performer Richard Hunt; the film is dedicated to both. There’s an emotional weight to the production that transcends the Muppets’ usual cheerful anarchy. Jim Henson had died unexpectedly in 1990, and his children were navigating how to continue their father’s legacy. The Muppet Christmas Carol became not just a film but a statement: the Muppets would survive, and they would honour Jim’s memory by doing what he did best, creating entertainment that worked for both children and adults.

The songs by Paul Williams are memorable, from the jaunty “One More Sleep ‘Til Christmas” to the emotional “Bless Us All” to the haunting “When Love Is Gone” (cut from the theatrical release but restored in recent editions). Paul Williams said of the experience: “I sat on a bench and Scrooge’s song suddenly started coming to me… I think I got as far as ‘There goes Mr Humbug, there goes Mr Grim / If they gave a prize for being mean, the winner would be him’ before I paused at all”.

The film’s initial box office was modest. The film opened in sixth place, initially reported to have collected $5.9 million in box office estimates, which was later revised to $5 million, ultimately grossing a total of $27.3 million in North America, having to compete with Home Alone 2 and Disney’s own Aladdin. But like the 1951 version, The Muppet Christmas Carol found its audience through home video and television broadcasts, eventually becoming a perennial favourite.

The Muppet Christmas Carol is considered one of the most accurate film adaptations of Dickens’s novella, thanks to its faithful use of original text, Michael Caine’s serious portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge, and the film’s blend of direct quotations, thematic fidelity, and whimsical Muppet humour. Many Dickens scholars and Victorian literature experts cite it as their favourite adaptation, praising how it makes Dickens accessible to children while never condescending to the material.

The film’s cultural impact extends beyond entertainment. The idea of “keeping Christmas” is an invitation and a challenge to consider what Christmas really means to us, not just celebrating on 25th December, but carrying that spirit of generosity and connection throughout the year. This message, central to Dickens, shines through particularly clearly in the Muppets’ interpretation.

Other Notable Adaptations Worth Mentioning

The landscape of Christmas Carol adaptations is vast, and several other versions deserve recognition:

Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983): This 26-minute Disney short featured Mickey Mouse as Bob Cratchit, Scrooge McDuck as Ebenezer Scrooge (essentially the role he was born to play), and a cast of classic Disney characters. Brief but charming, it introduced Dickens’s story to a new generation of children.

Patrick Stewart’s Version (1999): This TNT production, adapted from Stewart’s acclaimed one-man stage show, is often cited as the most accurate A Christmas Carol movie thanks to its natural dialogue, tone and structure. Stewart, himself a Shakespearean actor of the highest calibre, brought depth and nuance to Scrooge while maintaining close fidelity to Dickens’s text. The use of digital special effects, then cutting-edge, created some of the most convincing ghosts yet filmed.

Robert Zemeckis’s Motion Capture Version (2009): Directed by Robert Zemeckis and featuring Jim Carrey in multiple roles (Scrooge and all three ghosts), this ambitious film used performance-capture technology to create an animated world that straddled the line between realistic and stylised. The 2009 Jim Carrey film stays remarkably close to Dickens’s text, although it adds some modern visuals and action sequences. The film’s dark tone and occasionally nightmarish imagery made it less suitable for young children, but many praised its visual ambition and Carrey’s performance. Critics were divided on whether the technology enhanced or distracted from the story.

Why These Films Endure

What explains the endless appetite for new versions of this 180-year-old story? Part of the answer lies in the tale’s fundamental structure, it’s essentially three short films within a frame story, allowing each adaptation to emphasise different periods of Scrooge’s life and create distinct visual styles for each ghost. This built-in variety prevents the story from becoming monotonous.

But there’s something deeper at work. Each generation seems to need its own Christmas Carol, reflecting contemporary concerns while maintaining the story’s core message. The 1951 version spoke to post-war Britain’s anxieties about poverty and class. The 1984 version captured Reagan-era concerns about greed and social indifference. Scrooged satirised media culture and commercialisation. The Muppet Christmas Carol offered comfort and continuity after Jim Henson’s death.

These films succeed because they understand that Dickens wrote not just a ghost story or a Christmas tale, but a moral fable about human possibility, the idea that people can change, that redemption is always available, that it’s never too late to become better. In a cynical age, this optimism remains powerfully appealing.

The technical advantages of film, its ability to visualise the supernatural, to capture emotional nuance in close-up, to use music and editing to manipulate time, make it the perfect medium for A Christmas Carol. The story was written in 1843, but it might as well have been designed for cinema.

The Competition Continues

As of 2025, new adaptations continue to appear. There have been adaptations featuring anthropomorphic animals, modern retellings with female Scrooges, musical versions, and countless variations on the basic template. Television Christmas specials regularly feature their own takes, everyone from the Flintstones to Beavis and Butt-head has done a Christmas Carol episode.

Yet despite this saturation, audiences keep returning to the classic versions. The 1951 Alastair Sim film, now over 70 years old, still airs every December. The George C. Scott version has found new audiences through streaming. The Muppet Christmas Carol has become a millennial and Gen-Z favourite, with fans celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2022. Scrooged has achieved cult classic status as the alternative Christmas movie for those who find traditional holiday films too sweet.

These films have achieved something remarkable: they’ve become part of how we experience Christmas itself. For many families, watching one or more versions of A Christmas Carol is as much a holiday tradition as decorating trees or exchanging gifts. The films have outlasted changing technologies, evolving tastes, and the rise and fall of the actors and filmmakers who created them.

In adapting Dickens’s novella, these filmmakers didn’t just create movies, they created traditions, touchstones, and annual rituals. They gave us multiple ways to experience the same story, each emphasising different themes and appealing to different sensibilities. Some prefer the atmospheric gloom of the 1951 version, others the dangerous edge of the 1984 film, still others the warmth and humour of the Muppets or the satirical bite of Scrooged.

The remarkable thing is that all these interpretations can coexist. We don’t need to choose a definitive version because each serves a different purpose and speaks to different aspects of Dickens’s multifaceted story. Together, they form a cinematic Christmas carol of their own, variations on a theme, each adding its own voice to the chorus while singing the same essential song of redemption, compassion, and hope.

As long as people gather during the holidays to watch stories of transformation and second chances, as long as we believe that the worst among us might yet become better, these films will endure. They remind us, as Dickens did, that Christmas, at its best, is not about presents or decorations, but about recognising our shared humanity and choosing, every day, to keep Christmas in our hearts.

Leave a Reply